The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals. Sign up today!

THE OTHER F-WORD

As America looks for more energy resources, the word “fracking” has become part of the lexicon. But what does it really mean?

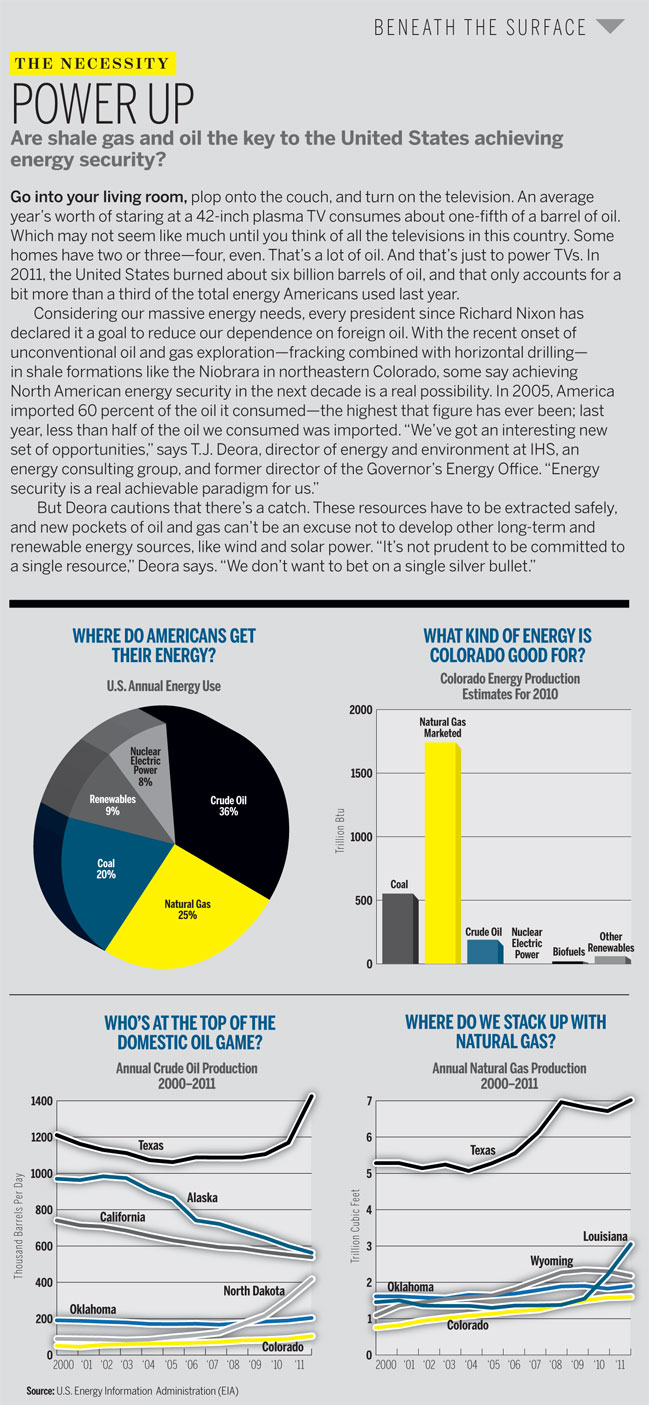

There it is, that word—frack—with just two small letters separating it from one of the most vulgar, reviled words in the English language. We read about fracking in newspapers; we see it on the evening news; we hear it in political stump speeches. And, you know what? It’s difficult to know what to think. The industry calls it a modern oil and gas revolution. Others argue that fracking is creating health problems today—and that we have no idea what sorts of issues will pop up 10, 20, 30 years from now. One thing is certain: Fracking has become one of the most contentious debates of our time. Before we dig into some of these issues, let’s get one thing straight: What is fracking, anyway? • “Fracking” is shorthand for “hydraulic fracturing,” a process used to extract oil and gas locked in dense rock formations thousands of feet beneath Earth’s surface. In order to unlock these resources, companies inject a cocktail of water, sand, and chemicals underground at an extremely high pressure, which fractures the dense rock and allows the oil and gas to seep from those fissures to the surface. A version of this process was first attempted in 1947 in an oil well in southwestern Kansas, not far from the Colorado border. • Since then, the fracking process has evolved, and perhaps more important, drilling techniques have evolved, too. In the past decade or so, oil and gas companies have developed what’s known as horizontal drilling, in which they drill vertically into the ground, hang a right, and continue drilling parallel to the surface for up to two miles. Sometime around 2005, when oil and gas companies began fracking horizontal wells, production started to boom. Long, narrow, and dense rock formations that were previously inaccessible sprouted bull’s-eyes. • In this package, we examine this complicated, controversial procedure, and many of the questions it raises. Will fracking lead us to energy independence? Or will it drive us farther down the road to environmental armageddon? As Colorado continues to be at the forefront of hydraulic fracturing in the United States, the answers to these questions, and many others, will be central not only to energy policy in the coming years, but also to the health and well-being of the people fracking affects.

Frack vs. Frac

Even the spelling of the word “frack” is controversial: Oil and gas industry folks, geologists, and linguists make the case that the accurate way to shorten the term “fracture” is “frac.” No “k.” That would mean that the shorthand would be “fracing,” or, for purists, the contraction “frac’ing.”

Of course, English is a strange language, and, right or wrong, “fracking” has become the most commonly used spelling of the term. Critics say that this version is just a tool employed by environmentalists and protestors to perpetuate their negative campaign by associating “frack” with…well, you know what.

For Love Of A Son

A small-town mom fights big-time fracking to protect her child’s health.

It was about a year ago when Angie Nordstrum first learned about the eight oil and gas wells planned less than 800 yards from her son’s school, Red Hawk Elementary, in Erie, Colorado. Two other schools and an early childhood learning center were nearby. Drilling for natural gas is not new for the town of 18,500, which straddles Boulder and Weld counties at the edge of the mineral-heavy Wattenberg Field and is home to 208 active wells. Nor was the drilling company’s presence new; Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. owns 1,100 wells in Weld County. Nearly all wells are hydraulically fractured after drilling is completed.

Nordstrum, 41, might never have cared—except that she had no choice. Eight years earlier, she’d been diagnosed with thyroid cancer while she was expecting her only child. She underwent surgery, but postponed her radiation treatments during pregnancy. In 2004 she gave birth—only to watch her son, during the first year of his life, develop the kinds of allergies that give parents nightmares. There were only about 10 foods on the planet he could eat without risking a reaction, and he couldn’t run around a school field because the smallest trace of whatever was sprayed on the grass left his skin with surface burns. (Nordstrum was treated for her cancer after she finished nine months of nursing, and has been cancer-free since 2010.) There was no way the boy could go to school. Instead, he learned and played in a “bubble” at home—a safe zone where he could grow up in a pollutant- and chemical-free environment.

Today, although her son has outgrown some of his allergies, Nordstrum hasn’t stopped being hyperaware of environmental hazards. That’s why Red Hawk seemed like a good choice when he finally enrolled in school as a first-grader. The sleek, two-story building, built in 2011, is LEED-certified for sustainability with features like low-flow plumbing for water conservation, nontoxic finishes, and outdoor classrooms that teach students about Colorado’s natural environment. Part of its core vision is “celebrating multiple perspectives along with developing a sense of environmental responsibility that includes personal development and physical well-being.”

Nordstrum was stunned when she learned what the hydraulic fracturing, within sight of her son’s school, would entail. A mixture of chemicals, water, and sand would be pumped into the ground under extreme pressure to fracture the rock and release the trapped gas—and those chemicals could include carcinogens and other toxins. Industrial equipment, diesel truck traffic, and noise pollution would accompany the operation; the access route to the drilling site, called Canyon Creek, passed right in front of Red Hawk, where kids rode their bikes, got dropped off, and walked to and from school. This route would be used to cart tanks of waste away from the site.

The more people Nordstrum spoke with around Erie, the more alarming things she heard: kids having regular 20-minute bloody noses and people with chronic headaches. Several people on her own block had their gall bladders removed. Could they prove causality? No. Still, they believed the health issues could possibly be related to the drilling and fracking that had become pervasive in Erie and farther east into Weld County. Together with a handful of other concerned parents, Nordstrum founded a grassroots advocacy group called Erie Rising.

In January 2012, Erie Rising gathered about 100 people at an Erie Board of Trustees meeting to express its concerns. Two months later, the town imposed a six-month moratorium on new drilling permits so experts could investigate and analyze data to better inform oil and gas related decisions. But permits had already been issued for the site near Red Hawk, so drilling and fracking would proceed there as planned. “It’s so violating to all of us,” Nordstrum says. “I’ve lived here for 10 years. I picked this community because of the family potential. We’ve got wonderful amenities: a rec center, library, trails, all within walking distance. We should be able to enjoy it.”

Encana suggests that the argument is moot because the company had approval to access that site before the school was built. Furthermore, Wendy Wiedenbeck, Encana’s community-relations advisor, says the so-called “fractivists” are creating hysteria based on unproven theories. “This doesn’t mean they don’t have genuine concerns, and that we don’t have a responsibility to listen,” Wiedenbeck says. “But to bring about change, we have to do it based on fact, not fear.” Encana fulfilled its promise to complete its drilling and fracking before the first day of school and says it has changed its schedule to avoid the busiest school hours. Most recently, the company found an alternate route to access the site that doesn’t encroach on Red Hawk Elementary.

On mother’s day 2012, a couple of weeks before drilling was set to start, Nordstrum sent a letter to the top executives at Encana—the letter was also published in Boulder’s Daily Camera—that, in part, called for a halt to Encana’s operations at Canyon Creek:

Our wish is that our children attend schools where they are not at risk of toxic chemical exposure, subterranean radioactive substances and toxic metals. Our wish is that our children get to harvest tomatoes and lettuce from their organic school garden; fresh produce that has not been contaminated by chemical-laden air particles. Our wish is for our children to play tetherball on the playground without having difficulty breathing. Our wish is that our children will not suffer from fracking chemical–related nosebleeds. Our wish is that our children will grow up cancer-free.

Nordstrum says no one from the company responded to her.

When the six-month ban expired in September, the town of Erie chose not to renew it. Erie Mayor Joe Wilson says a third-party partial analysis for which the town paid disputes much of the activist rhetoric about Erie’s air quality and toxicity levels. Ultimately, the town entered into a Memorandum of Understanding with Encana and fellow oil and gas operator Anadarko Petroleum Corporation. The agreement requires, among other things, that the companies use the newest, cleanest technology available to eliminate toxic leakage.

The Canyon Creek wells by Red Hawk Elementary are currently “in production,” meaning they’re producing natural gas—and could continue doing so for up to 30 years. Sometimes Nordstrum’s son comes home from school and tells her not about his spelling or math test, but about the big trucks he saw at the drill site—which is what he sees when he looks out his school windows. She still recalls finding a coat of white dust—a lab test confirmed it was silica dust, a toxic byproduct of fracking—near the vegetable garden outside Red Hawk. “It has been so consuming of my life,” Nordstrum says. “I don’t think a lot of people grasp the gravity until it happens right next to their kid’s school. I try to be careful of not scaring him. And I try to portray that what’s going on in our community isn’t right—that it’s important to stand up for what we believe in.”

State of change

A quick look at the state rules that regulate fracking.

Oil and gas operators are required to inventory the chemicals at each well site, notify the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) 48 hours before any frack job, and monitor the well pressure during the fracking process. As of April 2012, Colorado became one of the first states to require its operators to disclose the chemicals in their solutions within 60 days of completing a frack job. “Colorado’s disclosure rule isn’t perfect, but it’s a good step in the right direction,” says Earthjustice attorney Mike Freeman. “The idea is that before you can even figure out how big of a problem fracking is, you need to know what they’re using.”

What’s next?

Setbacks are one of the hottest fracking debate topics in Colorado. The current rules require a drill pad to be set back 150 feet from a building, or 350 feet from buildings in high-density areas. In October, the COGCC launched a process, which may take up to three months, to consider changes to the existing setback rules.

Split Estate

How one family confronted fracking—and lost.

it was afternoon when Carol Bell first noticed the stake. She had just returned home from a trip to the grocery store. The wooden post protruded from the dirt not more than a few feet. There was a small orange flag near the top of the stake, which was just footsteps from a horse barn owned by Carol and her husband, Orlyn, and a few hundred feet from their home, both located on the Bells’ 110-acre ranch in Silt, Colorado. Carol felt ill the moment she saw the stake. It seemed that someone had fired a warning shot, unmistakably meant to convey one thing: We can do whatever we want.

In a way, Carol knew this was coming. Months earlier, a representative of Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. knocked on the Bells’ door and delivered the news. Like many landowners in Colorado, and across the country, the Bells owned the surface rights to their land, but not the rights to the subsurface minerals. Encana had leased the rights to those minerals and intended to drill on the ranch to extract natural gas beneath the ground. The Bells would have to provide Encana with “reasonable” access to the property.

Carol and Orlyn were worried. They weren’t anti-drilling, but derricks had been popping up all over Garfield County, and some residents were already complaining about the smell and the noise. But Encana was willing to negotiate, and the Bells figured they could find common ground. Then, Carol noticed the stake with the orange flag. It appeared that Encana didn’t intend to drill in some far-flung corner of the ranch; rather, it wanted to drill a few paces from the barn. Nothing about the location seemed “reasonable” to Carol.

The two parties—operator and landowner—set out to negotiate a surface use agreement, a contract that would indicate, among other things, where Encana would drill, how it would access the drill site, and what, if any, financial compensation the company would pay the Bells. The Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC), the agency that regulates drilling in the state, requires that operators consult with landowners before drilling. In negotiating with the Bells, Encana agreed to move the well pad away from the barn. The company also agreed, according to the Bells, to pay $2,500 per acre for access to the land. (Encana does not disclose specific amounts paid to landowners per company policy, but an Encana spokesperson says the Bells were paid “tens of thousands of dollars.”)

The Bells argued that the $2,500-per-acre offer would not cover the loss in value of their land. In response, they received a three-page letter from Encana that, in part, stated: “We believe we have fully satisfied Colorado law…where the Colorado courts recognize that ‘the owner of severed mineral estate or lessee is privileged to access the surface and use that portion of the surface estate that is reasonably necessary to develop the severed mineral interest.’?”

The final paragraph of the letter read: “Encana will not delay drilling these wells to further dispute the compensation matter.” Translation: This was the best deal the Bells were going to get—a deal Encana thought was more than reasonable. “We always try to take a fair approach,” says Encana public relations director Doug Hock. “I know they weren’t happy, but I think at the end of the day, it’s one of those things—we weren’t going to make them happy. Sometimes in business deals, that happens. The people who have production on their property—they’re having to put up with, let’s face it, a nuisance.”

Carol describes what followed those initial negotiations not as a nuisance, but as years of heartache. The traffic and noise were, at times, unbearable. It’s “like you’re inside a jet engine,” Orlyn says. The Bells say the air frequently smelled of gasoline. “They were putting out a lot of crap that we were breathing,” Carol says. There was a spill. Carol thinks it was diesel fuel; she took pictures to document what happened. She says it took days until someone cleaned up the mess—only for another spill to occur, and this time, she says, it was fracking fluid. Even the comparably little things were bothersome. More than once, a truck headed for the drill site on the ranch knocked over the Bells’ mailbox. Before the oil and gas development on the ranch, elk roamed the property, but after the drilling started, Carol says she didn’t see the animals anymore.

Carol traveled to Washington, D.C., to advocate for stricter regulation of oil and gas development, and she joined a local group that was also advocating for stricter regulation. She remembers at one point sitting around a table with a few friends and wondering, “Where is our Erin Brockovich?” But there was no Brockovich, and after three years, the Bells grew tired of fighting. The arrangement had changed their lifestyle. “You couldn’t look anywhere and not see them,” Carol says. So they started to talk about selling the property. The Bells had always talked about moving, but it wasn’t supposed to happen like this; they had wanted to stay on the ranch for another few years.

Word traveled fast. Before the Bells officially listed the land for sale, they had an offer. Ironically, a local man who worked for Encana purchased the ranch. The Bells moved to Fort Collins, where they live now. Seated in their living room, Carol recalls the struggle. She feels remorse for having left the community that she and her husband were part of for a quarter of a century. “When you realize you have no power,” Carol says, “giving up is a little easier.”

History Lesson

The genesis of split estates.

The concept of a split estate—a situation in which someone owns the surface rights to a piece of land and someone else owns the rights to the subsurface minerals—dates to the American Civil War. That’s when president Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act of 1862, which offered chunks of Western land to anyone who physically claimed the property. But in the early 1900s, Congress realized the minerals beneath the land it was handing out were valuable, and the government started to retain the rights to the minerals. Today, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) holds about 700 million acres of mineral rights, about 29 million of which are in Colorado. “It certainly is surprising to some,” says Denver-based attorney Jack Luellen. “You go out and buy a house in Greeley, and I think most people don’t know that anything below the house may not be theirs.”

[ The research ]

DISCOVERY ZONE

Recent studies specific to Colorado and the West suggest significant environmental side effects that could pose health risks to people living in proximity to oil and gas operations.

But, in the words of COGCC director Matt Lepore (see page 95), “there’s no such thing as a perfect study.”

• AIR QUALITY

The researchers: National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

What they studied: Greenhouse gas emissions

from natural gas drilling in northeastern Colorado/Weld County.

What they found: Natural gas extraction leaks twice as much methane—about four percent of the total extracted—into the atmosphere as previously estimated by the EPA. Methane, the primary component of natural gas, is 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide over 100 years. Other emissions, including the carcinogen benzene, are also likely being leaked at higher-than-expected rates.

Why it matters: Although natural gas may burn cleaner, the effect is diminished if methane and other toxins are escaping into the atmosphere during its extraction and processing.

The caveat: Most of the data were collected in 2008. Since that time, Colorado has imposed stricter air emissions rules: 84 percent of wells that have been hydraulically fractured since April 2012 have undergone “green completions” to reduce the amount of methane leaked. This is a new EPA rule that will take effect nationally by 2015 and is expected to save the industry $11 million to $19 million that year in natural gas previously “lost” to the atmosphere.

• HEALTH RISK

The researchers: Colorado School of Public Health, University of Colorado

What they studied: Health impacts from exposure to natural gas development in Garfield County.

What they found: People living closer to natural gas wells are at a greater risk for developing neurological and respiratory diseases than those who live farther away. “This hazard is greatest during the period of short-term, high emission that occurs during well completion,” says research associate Dr. Lisa McKenzie. The same is true for cancer odds, primarily due to benzene exposure: 10 in a million for residents near wells; six in a million otherwise.

Why it matters: Further refined data like this could be helpful for setback rules (the minimum distance from a building that an operator can drill).

The caveat: The EPA’s default methodology used here is designed to overestimate risks. And data were collected between 2008 and 2010 during uncontrolled flowback, meaning there was no technology to curb leaked emissions, so results may be inconsistent with how other wells operate today.

• GROUNDWATER

The researchers: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

What they studied: Groundwater contamination from natural gas fracking near Pavillion, Wyoming.

What they found: Hydraulic fracturing is linked to contamination of groundwater. In two wells, chemicals were present in amounts higher than the EPA’s drinking water standard.

Why it matters: Hydraulic fracturing was exempt from the EPA’s Safe Drinking Water Act. At the time, the industry claimed that groundwater contamination from fracking had never been proven.

The caveat: The U.S. Geological Survey, when called upon for additional sampling, claimed the EPA’s methodology was flawed and inconsistent with its own. The EPA has defended its findings.

_____

Getting Dirty

Three ways fracking could contaminate drinking water.

1. Surface Spill

Someone handling fracking fluid could spill that fluid, which could then seep into the ground or leak into a stream or river. It’s also possible that fracking fluid could leak from a faulty storage tank or truck while it’s being transported. There have been a total of 1,658 reported spills in Colorado since 2009.

2. Well Casing

Companies use millions of pounds of steel and cement to reinforce the part of the well that passes through freshwater sources. If the encasement is not properly constructed or fails, fracking fluid could leak into an aquifer.

3. Migration

The cracks created in shale rock during the fracking process could extend farther than anyone realizes, thus creating an underground pathway for fracking fluid or natural gas to travel up into an aquifer. This migration is still largely a theory.

Making the Rules

Why the Environmental Protection Agency doesn’t regulate fracking.

It may come as a surprise that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—the key federal department tasked with protecting our environment—does not regulate hydraulic fracturing. In 2005, Congress passed the Energy Policy Act, which, among other things, exempted fracking from the rules of the Safe Drinking Water Act. The provision was tacked onto the energy bill in the middle of the night, says U.S. Rep. Diana DeGette, D-Denver. By the time the act came to a vote, DeGette says few legislators realized the exemption existed.

The provision is known as the “Halliburton loophole.” (Former Vice President Dick Cheney,

a one-time Halliburton executive, helped draft it.) The White House cited a 2004 EPA report that said fracking posed “little or no risk” to drinking water. DeGette and others have since questioned that document. In May of last year, Ben Grumbles, an EPA official who signed off on the report, wrote, “EPA, however, never intended for the report to be interpreted as a perpetual clean bill of health for fracking or to justify a broad statutory exemption from any future regulation.” In every session of Congress since 2006, DeGette has introduced the FRAC Act, to close the loophole. “There are some people who say that fracking should be banned,” she says. “I’m not in that camp. I think there should be appropriate environmental controls.”

The EPA is currently conducting a new hydraulic fracturing study, due in 2014; An early report hits this month.

_____

The Boss Man

Four questions for Matt Lepore, director of the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC).

What is the biggest challenge the COGCC faces?

Fulfilling the [twofold] legislative mandate that we have: The last 60 years, the state General Assembly has said it is in our best interests to produce these resources—but that it must be done responsibly. I don’t want to say they’re internally inconsistent, but they require us to balance two different interests.

How is your relationship with the oil and gas companies?

They run the gamut from the most sophisticated, biggest, and well-capitalized to small, undercapitalized mom-and-pop-type operations. Our relationship with them varies. Some operators work to the highest standard, hire the most competent people, the best contractors, and are very attuned to their social responsibilities; we generally have a good relationship with them.

How do you handle social upheaval and address citizen concerns?

There are inherent incompatibilities with having an industrial activity close to a school or an area like that. At the same time, I don’t see evidence of the dramatic health effects some citizens allude to. With respect to hydraulic fracturing, the chemicals used are essentially familiar.

Diesel fumes are a significant product of multistage fracking. We understand the concerns, but diesel emissions are somewhat ubiquitous in an industrial world. We all are exposed to diesel from traffic, trains, and other sources. There are benzene emissions from automobiles, or the gasoline pump. I don’t mean to dismiss citizens’ concerns. But I think they need to be put into the context of everyday life in a world that’s highly modernized. I would not choose to live 350 feet from an oil and gas well. But I would not be concerned about my health or my children’s health.

Have you heard the suggestion that this situation resembles Rocky Flats?

I think it’s apples and oranges. Everyone knew then that plutonium was not good. Oil and gas—it’s not plutonium. Benzene: It is known to be a carcinogen, but it doesn’t persist in the environment the same way plutonium does. I understand that people can say that we can’t understand the long-term. [But] we’ve been bringing oil and gas out of the ground since the late 1800s. We’ve figured out how to do this.

Jurisdiction Matters

Longmont steps up in the power struggle between local and state governments: Who should regulate fracking?

Imagine someone coming into your backyard and building a factory in full view of your living room. They tell you the location is prime for manufacturing. But no one cares that you know your neighborhood best. There’s nothing you can do about it. The factory starts humming. Workers traipse through your yard every day. Smog wafts up over your rooftop.

It’s not a far-fetched scenario for those who live in mineral-rich zones. Currently, the state makes the oil and gas rules for Colorado. Municipalities, much to the frustration of some, don’t have the final say on the technical aspects of drilling within their city limits.

And then, there’s Longmont. At press time, the city of Longmont and the state of Colorado were locked in a legal skirmish. The state sued the city in July after Longmont passed its own drilling regulations in an attempt to trump the COGCC’s existing rules. “To be clear at the outset,” wrote Governor John Hickenlooper in a September 26 letter to Longmont city officials, “suing Longmont was a last—and not a first—resort for our administration. This decision was only made after attempts to resolve the state’s concerns were unsuccessful.”

The state’s beef? A “patchwork” of local, inexperienced town governments managing different sets of regulations is unwieldy and inefficient compared to an agency with more than 70 years of oil and gas experience and already-existing rules that are “widely regarded as among the most protective in the nation,” Hickenlooper wrote. The city of Longmont filed to dismiss the lawsuit in September, to no avail. The case has become a textbook example of the regulatory debate sparked by hydraulic fracturing.

Litigation aside, the residents of Longmont last month voted yes on Question 300, a ballot initiative making Longmont the first city in Colorado to ban fracking and related waste disposal within city limits. The charter amendment was petitioned onto the ballot by advocacy group Our Health, Our Future, Our Longmont, which secured 8,200 signatures. Some critics say the amendment will just invite further legal action.

Take Two

Doing it different in the East.

New York has taken a drastically different approach to hydraulic fracturing than most states, Colorado included. In 2008, New York officials temporarily banned fracking in the Marcellus shale—a formation that, by some estimates, contains enough natural gas to meet the country’s demand for six years. At the same time, the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation started researching the impact fracking has on the environment. The governor has said he intends to continue the temporary ban until the study is complete. In the meantime, more than 30 towns in New York have banned fracking permanently, and at least another 80 have enacted temporary moratoriums in line with the state’s decision.

On The Big Screen

Three films tell three very different fracking stories.

• Gasland

If you haven’t seen the Oscar-nominated documentary Gasland, chances are you have heard of the film’s money shot, in which a Colorado man sets fire to the water running out of his kitchen faucet. The scene—and the implication that fracking caused the flammable tap water—became so controversial that the COGCC issued a detailed, four-page Gasland correction document. The agency contends that the gas in the tap water is naturally occurring “biogenic” methane—not the “thermogenic” methane associated with oil and gas development. Film director Josh Fox responded with the argument that fracking could have created a pathway for “biogenic” methane to seep into the aquifer. Who’s right? Who knows? gaslandthemovie.com

• FrackNation

FrackNation is a response to Gasland that aims to “tell the truth about fracking for natural gas in the United States and globally.” The film challenges fractivist rhetoric with testimonies from families and citizens whose survival depends on hydraulic fracturing—e.g., farmers whose livelihoods hinge on leasing their land to oil and gas companies. The filmmakers have also produced documentaries that attack Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth and aim to debunk the environmentalist movement. FrackNation is currently in production. fracknation.com

• Promised Land

Matt Damon is stirring up controversy—and talk of an Oscar—with his latest film, a drama that pits a natural gas company salesman against a small rural town struggling with economic collapse. The twist: The film, which reportedly carries an anti-fracking message aligned with Damon’s and co-star John Krasinski’s views, is financially backed by Image Nation Abu Dhabi, which is owned by the government of Abu Dhabi, capital of the United Arab Emirates—an OPEC member and the world’s third-largest oil exporter. Promised Land premieres this month so it can slide into the 2013 Academy Awards pool; look for the general release in January.

Fort Lupton, USA

The town that oil and gas built.

fort lupton, population 7,500, sits 16 miles east of Erie in the heart of the oil and gas boom in Weld County. Grannies Diner has a prominent spot on the main drag, Denver Avenue. Across from the diner, there’s a bar called Station Three Inc. A sign on the door says the bar opens at noon, but on a recent weekday morning around 11 a.m., there are two people inside sipping on frosted mugs filled with yellow beer. The Fort Lupton town hall is a few blocks south. Four large flags representing the United States, Colorado, the U.S. military, and Fort Lupton tower over the modest single-story brick building. Next to the town hall, there’s a parking lot, which has one reserved space. A placard claiming the spot reads “Mayor Tommy Holton.”

Holton has a tall and commanding presence, with a bushy gray mustache that turns down and stretches toward his chin, like any good hero in a Western flick. It’s immediately clear that Holton likes the $10-a-day gig as mayor. He grew up in this town, and his wife was raised here. They were high school sweethearts. Holton’s parents own a farm just outside of Fort Lupton, where he lends a hand to supplement his mayoral salary. The Republican mayor is finishing his second two-year term and intends to run a third and final time. As he started his second stint two years ago, Holton decided to bet the house—and perhaps the fate of Fort Lupton—on the oil and gas business. That decision is paying off today.

For the past 40 years, Halliburton, a major oil field services provider, has operated a small facility just south of Fort Lupton. In 2010, the company announced it was looking to expand, and that it was considering moving to Greeley or Cheyenne, Wyoming. The problem was that the Fort Lupton site had been operating on a septic system. The company needed water and sewer to accommodate a bigger facility, and the town had yet to build the infrastructure. The way Holton tells it, when he heard Halliburton was thinking of leaving, he dialed a company executive and coaxed him into flying in from Houston for a meeting. “Basically on a handshake,” Holton says, the two parties struck a deal: Halliburton would fund the $2.4 million extension of water and sewer lines, and Fort Lupton would make sure the project was done in six months.

The new $40 million Halliburton facility is nearing completion, and Holton says the impact on the town has been noticeable. Halliburton has already added more than 700 jobs. Home values are up more than 60 percent, Holton says, while business in town has increased around 20 percent. An Italian restaurant with an unexpectedly trendy storefront opened down the street from Grannies Diner. Much of this, in Holton’s opinion, is thanks to Halliburton. “It’s been huge,” he says. “It has kept us from feeling a lot of the economic pushback.” In fact, Fort Lupton’s economy largely hinges on the oil and gas industry. Of the 25 largest employers in town, 10 are oil and gas related companies, and those companies have created at least 1,500 jobs—well-paying jobs. “It’s not inconceivable to make six figures with a high school education,” Holton says.

By some accounts, the oil and gas industry employs more than 100,000 Coloradans and pays a mean wage of $72,000 a year, which is 51 percent higher than the average Colorado salary. “If it hadn’t been for oil and gas,” says Holton, an appointee to the COGCC, “I think the economic downturn would have hit the Front Range a lot harder than it did.”

As for the controversy surrounding oil and gas development and hydraulic fracturing, Holton is convinced that the current regulations imposed on the industry are more than enough to keep the town safe. The way he sees it, it’s simple: “This is the most regulated industry in the state,” he says. “There are rules in place and we need to follow them. You can drill, but you need to do it right—if you screw up, take care of it.” Besides, he says, we’ve been fracking for years; after a while, you just don’t see it. “Being from here in Weld County—we don’t pay attention to that part of the landscape.”

Quenching the Thirst

How much water does fracking use?

Hydraulic fracturing isn’t just about chemicals. In Colorado, the process consumed 13 million gallons of water a day in 2011—enough to supply up to 60,000 families for a year. Sounds like a lot, but, in reality, it’s less than one tenth of one percent of Colorado’s total water usage. The greediest sector? Agriculture, which sucks up 85 percent of the state’s water. Yet oil and gas companies have even begun to outbid Colorado farmers during water surplus auctions. Where else does the water come from? Operators will often purchase from a provider such as the local municipality. But towns have the right to set their water prices higher for oil and gas companies. For example, operators in Erie now pay the town a premium over what other consumers pay for the same water. By 2015, projections say the state’s frack jobs will require daily water use that’ll roughly double what a 1,000-megawatt coal-fired power plant consumes every day.