The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals. Sign up today!

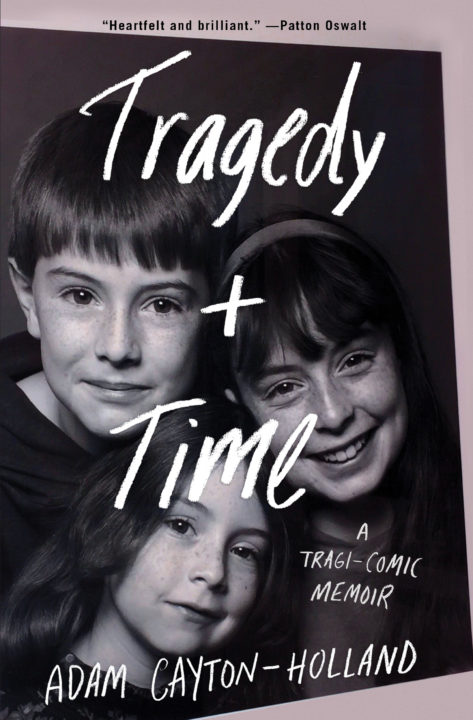

Being funny had gotten Adam Cayton-Holland far. He’d become an accomplished stand-up comedian, a member of the pioneering local trio the Grawlix, and a founder of the High Plains Comedy Festival, which returns to Denver for its sixth annual edition on August 23. Then, in 2012, just as he was about to grasp every comic’s dream—a sitcom—Cayton-Holland’s younger sister, Lydia, died by suicide. In his first book, Tragedy Plus Time: A Tragic-Comic Memoir (Touchstone, August 21), Cayton-Holland largely sets humor aside to address his own battle with depression, his sister’s death, and his family’s painful journey to reconcile Lydia’s premature passing. We spoke with Cayton-Holland to find out how someone who makes a living with laughter deals with such tragedy.

Resumé

Name: Adam Cayton-Holland

Age: 38

Seen Him In: Those Who Can’t, a sitcom about inept teachers at a fictional Denver high school. Its third season hits truTV later this year.

5280: Many comics, such as Robin Williams, have struggled with depression. Do you think comedy and depression are somehow linked?

Adam Cayton-Holland: I think good art comes from people who are sensitive. A lot of comics act tough, but they’re sensitive, which might mean they are more in tune with their feelings—aka depression.

Has your art changed since Lydia’s death?

First of all, it’s hard to call it an art when you make dick jokes. But that’s a tough one for me. I never talk about her onstage. Has darkness bled into my jokes? Certainly. But there was also darkness there before. I’ve never really attacked her death, though. This book was me talking about it.

Will you ever talk about her death during your act?

I don’t want to neglect it, but I just don’t talk about heavy things. I talk about meeting a member of the Wu Tang Clan. When only 15 percent of the audience knows who I am, am I going to cram in my most tragic life piece? Or am I going to be funny for a little while? If I’m at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, yeah, I’ll do an hour called “Lydia.” If I’m at the Des Moines Funny Bone, I’ll probably just play the hits.

Reading this book, I felt like you were searching for some kind of answer. Did you find it?

I was shocked Lydia did it. I thought she was close enough to tell me, I’m thinking about doing this, and we would have worked it out. So there’s anger. In the book, I tried to portray Lydia as the most empathetic of everyone in our family. She couldn’t stand suffering, and she knew doing this would make us suffer. For her to do it anyway shows me the level of desperation she was at. When I realized that, I had to forgive her.

Courtesy photo.So you have been able to forgive her?

Definitely. But that was the first reaction—anger. Especially when you see the damage it causes your family. You’re angry as fuck. You’re like, Come on, you did this to our parents? This is their last years of life and they have to deal with this? Not to be cheesy, but the love [for Lydia] just pushed the anger out of the way.

The book details how draining mental illness can be on friends and family. Do you have any advice for people with a loved one dealing with depression?

I’ve been talking to this dude named Adam Becker at the Mental Health Center of Denver, because I keep doing fundraisers for them and like the cause, obviously. He says it’s OK to be exasperated with a person who’s constantly depressed. It doesn’t make you a bad person. It’s trying when someone is down all the time and you’re trying to lift them up and they’re not lifting up. And it’s hard to not have blinders on about the severity of the problem. Looking back on it, Lydia overdosed twice. How did we not see this coming? So I think, if anything, my advice would be: Do more. If you’re exasperated, go out with your other siblings and bitch about her. But do more.