The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

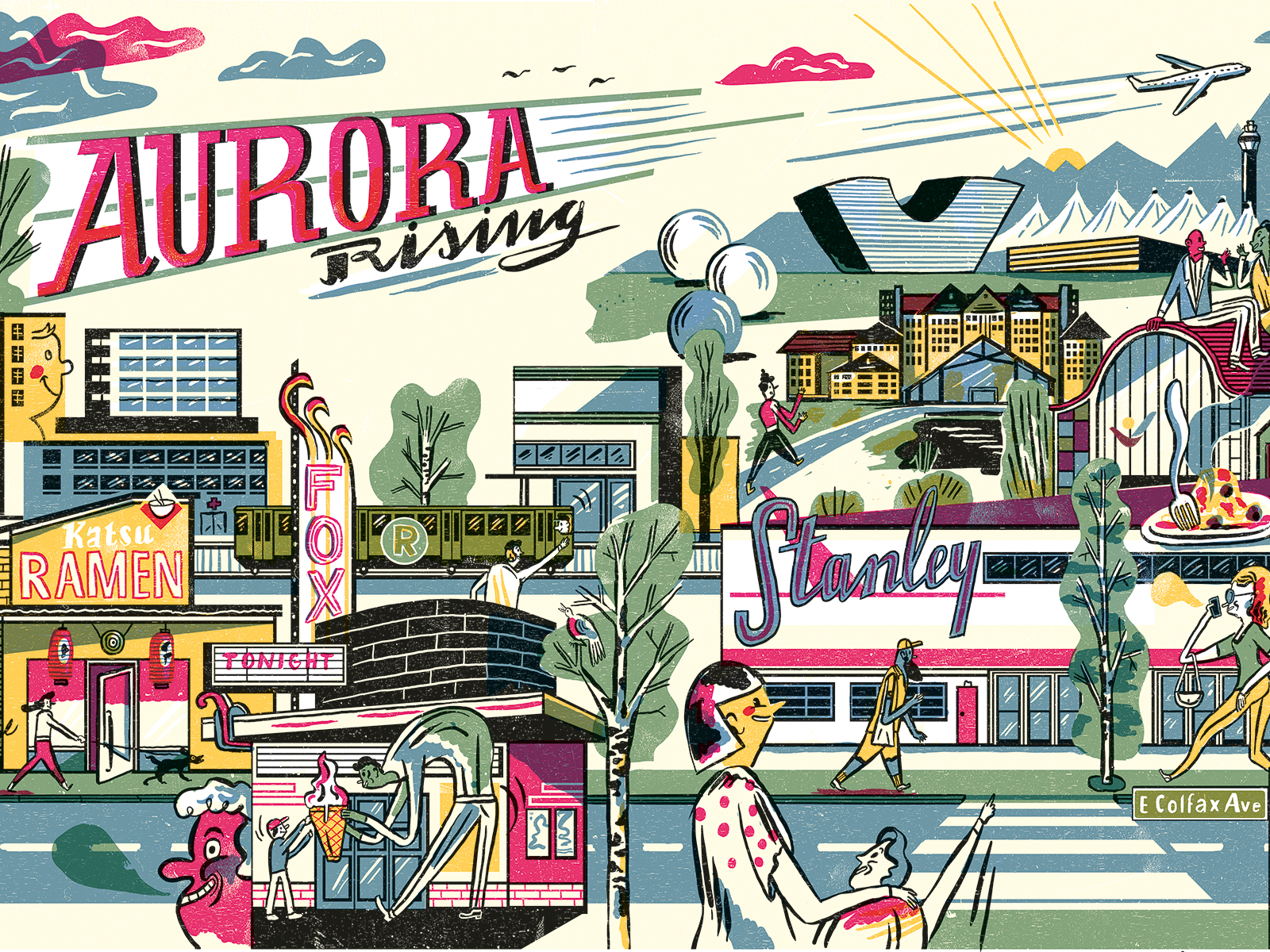

On Friday nights, Stanley Marketplace thrums with the sounds of hipsters and families purchasing locally made products before noshing on tacos, empanadas, and sushi. During weekends, Havana Street restaurants are packed with millennials slurping steaming bowls of pho and scooping up beef stew with injera. Synagogues and mosques are packed with congregants. Above it all, planes approach and depart nearby Denver International Airport (DIA) with a regularity by which you can set your watch.

Yes, Aurora is experiencing a new dawn—and it is nearly 30 years in the making. In late 1989, politicos broke ground at what would become DIA. The idea to stick Denver’s airport in what was essentially the middle of nowhere was sold to neighboring municipalities as an economic win-win for everyone. While the entire Mile High City metro area waited for DIA to take off, Aurora put its own growth plans into motion.

Today, Aurora continues to annex land and equals Denver in size. The area around the airport will add thousands of homes in the next 10 years. And the Gaylord Rockies Resort & Convention Center, a 1.9-million-square-foot building that opened this past December, is the latest step in a realization of Aurora’s regional influence and economic prowess.

But with growth comes change, and the city is not immune to the aftershocks of Colorado’s population surge. Displaced residents from other parts of the region have moved to Aurora because of its reputation for affordable homes, thus driving housing prices up across the city. The demographics have changed, too. Once a mostly white and aging city, Aurora is now the state’s most diverse, and the median age is 34.5 years old.

All of which means city leaders and influencers are spending a lot of time looking inward. “Aurora, historically, has had a small-town mentality,” says at-large Aurora City Council member Allison Hiltz. “We’re at this precipice where we get to decide what we’re going to be when we grow up.” What will fill in the open prairie? What will continue to attract new arrivals to the city? What will convince corporations to move headquarters and jobs there? And what will make longtime residents stick around for Aurora’s next act?

Mr. Aurora

Can the city’s next mayor live up to Steve Hogan’s distinguished legacy?

Aurora lost its biggest promoter when then Mayor Steve Hogan (pictured) died on May 13, 2018, shortly after being diagnosed with cancer. Hogan had served the city for more than three decades as a state legislator, City Council member, and, finally, mayor. Known to many as simply “Mr. Aurora,” his death left a void. That’s about to change: In November, Aurora residents will choose a new mayor at a critical moment—and there are plenty of people interested in the gig, including former U.S. Representative Mike Coffman, former City Council member Ryan Frazier, Aurora NAACP president Omar Montgomery, and current City Council member Marsha Berzins. To the victor: Hogan’s legacy and the chance to transform the city.

Prairie Patchwork

The plains east of Denver, once open grassland, are becoming more populated—and are gaining the businesses and infrastructure that cities acquire as they come into their own.

Aurora by the Numbers

97

City parks

160

Aurora’s area, in square miles

10

R Line light-rail stops in Aurora

6,229

Aurora’s highest elevation, in feet

The Gaylord Effect

Aurora’s biggest hotel just might change everything.

You probably couldn’t find a better view of the Front Range on December 18, 2018, than the one from inside the Gaylord Rockies Resort & Convention Center in Aurora. The nine-story atrium windows framed the powder-capped peaks and downtown Denver’s skyline. If you had looked closely, you’d have noticed that the massive window is made up of smaller glass panes. Thin black lines meet at each of the corners, like crosshairs in the eyepiece of a telescope. It was almost as if the building itself was bringing the vista into focus.

Years earlier, it wasn’t at all clear the project would ever happen. There was the Great Recession. The National Western Stock Show suggested it might move near the complex, which in turn fostered a campaign to keep the iconic event in central Denver. The original hotel developer pulled out. And in 2013, downtown Denver hotels sued over competition and public financing concerns.

Despite myriad hurdles, the ribbon was cut on that winter day in 2018, and the Gaylord Rockies was finally open for business. The economic impact was already clear: 1.1 million room nights had been booked (through 2028) before the first day. The bulk of those—80 percent—were for conventions that have never been to Colorado. Estimates suggest that the complex could add $273 million annually to the economy.

The place itself is enormous: 1,501 rooms with 485,000 square feet of meeting space built on 85 acres. The atrium is so big it was built around a restored (decorative) railroad car, and the sports bar features a TV that measures 14 by 75 feet.

Aurora’s leaders, though, might be less excited about size and more excited about what will come next; they point to how each of the other four Gaylord properties (in Tennessee, Florida, Texas, and Maryland) have created a building boom around them. If that happens in Aurora, the city may finally fill in its northern border and create a so-called aerotropolis. It’s not a new idea. Airports across the globe are developing mini cities around them focused on proximity to runways instead of nearness to a downtown.

That was part of Denver’s long-ago promise to neighboring areas: that if the capital could annex land for the airport and benefit from its economic potential, other towns would get to build out homes and retail around it. (In 2015, voters agreed to amend that original agreement to allow Denver to do some limited, nonresidential building on 1,500 acres near I-70.) The bulk of the to-be-developed land is not part of the Mile High City. “This Gaylord project is an incubator of opportunity for the whole area,” says Bruce Dalton, Visit Aurora’s president and CEO.

Which is why, on the day of the groundbreaking, the must-see panorama wasn’t the mountains or the downtown skyline. The more important sight was of the acres of Aurora land that lie between Denver and the airport—the future home of several mixed-use developments, including Rockies Village (129 acres), Painted Prairie (628 acres), and High Point (1,800 acres). This was the view that was finally coming into focus for Aurora.

Dream Catchers

Wendy Mitchell brings big biz to Aurora.

When a corporation is looking for a new home, the person to call in Aurora is Wendy Mitchell, longtime president and CEO of the Aurora Economic Development Council (AEDC). “What we do is bring jobs for people,” Mitchell says. “We’re not landlocked, so we can go after these big fish.” And the AEDC has reeled in more than a few trophies (Amazon, Kärcher, and Walmart, to name just three of the biggest). Mitchell and her five-person team sell corporations and big employers on Aurora with promises of space, quick DIA connections, tax incentives, and the Colorado lifestyle. But the biggest factor is sometimes the city’s ability to keep projects on schedule. Time, after all, is money.

Take Two

Three Aurora projects that have turned old spaces into new destinations for the entire region.

New Use: Stanley Marketplace

Old Use: Manufacturing building

While Aurora’s urban renewal office was working to find a new use for a vacant 140,000-square-foot building in the Westerly Creek area, some Stapleton residents, including then social worker Mark Shaker, wanted to build a neighborhood beer garden. But when Shaker toured the warehouse, he and others started to envision something even bigger: a marketplace that could create a bridge between two cities. In the years since its opening, Stanley Marketplace has become home to more than 50 Colorado-based retailers and restaurants, including Caroline Glover’s award-winning Annette.

Big Plans: Westfield, one of Stanley Marketplace’s developers, is building a 168-unit residential development on the southern edge of the property, and Shaker is interested in working on a mixed-use project at nearby Montview Plaza (ideas include small, modular housing and a community land trust to keep rents affordable for current and future neighbors).

New Use: Village Exchange Center

Old Use: St. Matthew Lutheran Church

Attorney Amanda Blaurock was visiting her stepfather in 2016 when he told her the Lutheran church where he was a pastor was going to close because of an aging congregation. Blaurock started to ask about what else could be done with the land and came up with a plan for a cultural community center. The congregation deeded the property to the project, and the Village Exchange Center opened the next summer. The space is now home to 16 resident partners, including Global Bhutanese Community Colorado. On any given day, the building might host Muslim prayers, a Congolese congregation, and ESL classes.

Big Plans: Blaurock and her team have already raised $2.2 million to support the Village Exchange Center and its programs and have launched a capital campaign to renovate and build out the current church space. Their wish list includes a restaurant storefront to help foster food startups and a playground for an early education center.

New Use: Medical Center*

Old Use: Fitzsimons Army Medical Center

In the 1990s, Aurora was hit hard when the U.S. Department of Defense closed two military installations in the city: Lowry Air Force Base and Fitzsimons Army Medical Center. As Aurora contemplated what to do with Fitzsimons, the University of Colorado’s medical school was looking for a new home. The timing was fortuitous, and after CU made plans to head east, Children’s Hospital Colorado and the VA followed. CU has built a campus that has nearly 25,000 employees and houses hospitals, a medical school, and research facilities. An innovation community to the north hosts a number of private labs and residences.

Big Plans: Expect to see plenty of cranes at the medical complex for the near future. UCHealth is building a third inpatient tower, the innovation community continues to expand, and the campus broke ground in January on the 390,000-square-foot Anschutz Health Sciences Building, which will hold labs and classrooms.

*Including Children’s Hospital Colorado, CU Anschutz Medical Campus, Fitzsimons Innovation Community, the Rocky Mountain Regional Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital

Growing Pains

Aurora’s not immune to the boomtown problems affecting other parts of the region.

The Challenge: Finding water for a population that is poised to double.

A hundred years ago, developers in Colorado’s arid climate might have used divining rods to locate water sources. Nowadays, they could simply talk to Aurora Water. The utility service has built a reputation for wringing every last drop out of its water rights with ideas like Prairie Waters, a recyclable water project that allows the city to treat and reuse river water. The system cost $638 million, took three years to build, and served its first glass of H2O to the public in October 2010. Prairie Waters could eventually treat up to 50 million gallons a day (currently, the system’s capacity is about 10 million gallons a day). That’s still not enough to meet projected demand, so Aurora Water is looking for more solutions. Last year, the city announced it was paying $34 million for a water source at the shuttered London Mine in Park County, where 1,411 acre feet (an acre-foot of water can serve approximately 2.5 families annually) of snowmelt pools underground.

The Challenge: Keeping the city’s housing stock affordable.

The promise of space in a crowded metro area ensures that Aurora will continue to grow, but all that property comes at a cost. Lately, conversations about affordability have dominated city politics. Ward I City Council member Crystal Murillo, who represents the area that borders Denver and includes Aurora’s oldest neighborhoods, was elected in 2017 in part because of her promises to address affordable housing. Murillo’s district is also a renter’s community where, traditionally, immigrants and refugees have settled. Those renters are being priced out, which means they often move to newer parts of Aurora with fewer services and transportation options. “You can’t talk about growth without talking about displacement,” Murillo says.

In 2018, the council created a $1 million fund to address affordable housing, but many council members already agree it’s not enough and are looking for ways to entice, encourage, and enable developers to produce more diverse housing stock or to directly help displaced persons with moving costs and rent deposits. Others are talking about community land trusts or tiny homes. “It’s unfortunately a difficult subject because there’s not a one-size-fits-all solution,” says Ward V council member Bob Roth. “The average household income right now does not support the average home cost.”

Room to Grow

Aurora’s footprint just keeps getting bigger as the city continues to annex land—much of which is set for development.

Heart & Soul

Does Aurora need a downtown?

Ask a child to draw a picture of a city, and there’s a good chance the sketch will include a skyscraper. So what if a city—like Aurora—doesn’t have a skyline? Or, for that matter, an actual downtown?

As Aurora grew from a suburb into the nation’s 54th-largest city, a centralized hub never developed—but not for lack of trying. The original parts of Aurora, around East Colfax Avenue and near the Denver boundary, were the municipal center and heart of the city for decades. But in 2003, city services settled in a new municipal center near South Chambers Road and East Alameda Parkway. Here, too, there’s a possibility for a nucleus; in fact, 60 acres have been earmarked for just that purpose. The land is there, but the private industry interest in building skyscrapers on that property hasn’t materialized despite a nearby light-rail stop, quick access to I-225, and proximity to the city’s main government building.

An urban core could also develop at the proposed aerotropolis or along the E-470 corridor, but Charlie Richardson, longtime city attorney and now Ward IV’s City Council member, doesn’t believe any of those things are going to happen. “I think it is impossible for Aurora to have a downtown,” he says. “You can talk about it all day long, but it just can’t be done because of the size of the city.” So it appears as though Aurora will continue to lack the skyline that defines most cities and provides fodder for commemorative pint glasses, touristy T-shirts, and bumper stickers. And maybe that’s OK—or maybe the sketch envisioning an iconic downtown just hasn’t been drawn yet.

Conversation Starters

Quick takes on some of Aurora’s most pressing issues.

On first responders

Allison Hiltz, at-large City Council member: “Our fire department is underfunded.… A heart attack isn’t going to wait. A kid who has an allergic reaction can’t wait for someone to get there.”

On neighborhood planning

Nicole Johnston, Ward II City Council member: “Because we are so spread out, a lot of the developers said we would eventually have restaurants and retail in [certain] areas. That hasn’t happened in a lot of our developments.”

On Gentrification

Assétou Xango, Aurora’s Poet Laureate: “On a personal level, its impact on communities of color is constantly frustrating. There’s a sense of erasure for my body and my placement, and that frustrates me through and through.”

Destination: Home

Aurora has become a gathering spot for the country’s newest arrivals—and may become a national model.

When Iman Jodeh’s parents immigrated to the United States more than four decades ago, they wanted to settle in a place that felt familiar, and Colorado’s climate and geography reminded them a little of Palestine. Eventually, they moved to Aurora because it was an affordable place to live. So they created a home and raised their four kids there. They saw a future in Denver’s neighbor—and they weren’t alone. “Almost 40 years ago, the center of the Muslim community in Colorado actually moved from downtown [Denver] and bought land in Aurora because it was affordable,” says Jodeh, the first female spokesperson for the Colorado Muslim Society. “We projected for that growth, and we ended up building the largest mosque in the Rocky Mountain region.” Today, she says, about 30 languages or dialects are spoken at the mosque.

Her family’s story is a microcosm of the immigration trends that have made Aurora the state’s most diverse city. Emigrants and refugees from all over the world—including Mexico, Ethiopia, El Salvador, and South Korea—have transformed the city in a matter of decades. In 1970, the city’s residents were 97 percent white; today, Aurora is nearing minority-majority status. And, according to the city’s demographic estimates, the foreign-born population grew more than 50 percent between 2000 and 2016.

There are plenty of factors that determine why a city attracts new arrivals. Positive experiences filter back to home countries and through nonprofit networks that help settle refugees and immigrants. Word gets out that certain cities are more affordable, more open, more inclusive. State Senator Rhonda Fields credits late Mayor Steve Hogan for helping create an atmosphere of safety. “When he was mayor, I think we became much more aware that our city was much more diverse,” she says. “The city has not shied away and has not put up barriers of hate or discomfort around anyone who wants to be a citizen in the city of Aurora.”

In particular, Aurora has another selling point: About four years ago, it created an Office of International and Immigrant Affairs, managed by Ricardo Gambetta, to develop a citywide plan for how the city can better interact with Aurora’s newest arrivals. At first glance, that might seem like no big deal. But Aurora says it is the only city in the state that has an immigrant integration plan. Only a dozen or so cities in the country have one. The plan includes a focus on naturalization, “so the communities can participate in the social and political life of the city,” Gambetta says.

His office has recently expanded its services to include translation and interpretation help for all city staff. That means that if the planning department is holding a community meeting, it can request in advance that someone who speaks Bhutanese or other languages be there to help communicate with all members of the audience. It’s a daunting task, but it ensures that all Aurora residents can be involved in the city’s business, because, as Gambetta says: “For us, our international community is one of our most important assets.”

Aurora by the Numbers

374,154

Aurora’s population in 2018, estimated

1 in 5

Residents who are foreign-born

34.5

Median age of residents

160+

Languages spoken by students in Aurora schools

Renaissance Man

Aaron Vega intends to make the city-owned People’s Building a destination.

It’s a big dream, but the city hopes to transform the People’s Building, an old storefront, into a cultural powerhouse. The person hired to make that happen is Aaron Vega, who has experience working as a producer, performer, and event manager. The space is a “blank box,” Vega says, and is ideally suited for pop-up artistic performances. Because the seats in the flex room retract, performers can adjust the space to suit their needs. Vega admits the current programming is eclectic—from shadow puppetry to a Get Your Ears Swoll live music series—but that’s intentional. He’s taking inspiration from artistic incubators like New York City’s HERE Arts Center and La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club. “If we could be the La MaMa of the region,” Vega says with a laugh, “that’s my goal.” Don’t be fooled, though: He’s serious about doing just that.

Welcome to the Neighborhood

The Aurora Cultural Arts District (ACAD)—near East Colfax Avenue—is still growing, but it already boasts artist co-ops, galleries, and public art. See for yourself.

Watch a screen print being made with nontoxic inks at…

Red Delicious Press

9901 E. 16th Ave.

Catch a world premiere theater production at…

The Aurora Fox Arts Center

9900 E. Colfax Ave.

Catch a jazz set or Shakespeare reading at…

The People’s Building

9995 E. Colfax Ave.

Don’t miss the district’s Art in Public Places pieces, including Chris Weed’s steel chair at…

“Unglued”

East Colfax Avenue and Dallas Street

Rent a space to channel your inner Clyfford Still at…

ACAD Studios & Gallery

1400 Dallas St.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this feature mistakenly stated Aurora uses about 10 million gallons of water a day; total water usage for the city is about 46 million gallons per day.