The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals. Sign up today!

You’ve likely been hearing about Colorado’s redistricting process more than ever. That’s because the once-a-decade undertaking, which determines the boundaries for both congressional and state legislative districts, is going to look a bit different this go around.

In 2018, Colorado voters passed two ballot referendums, Amendments Y and Z, each with about 71 percent of the vote. The measures require the state to set up two independent commissions, one tasked with congressional redistricting and another with state legislative redistricting. Each commission features a 12-member panel composed of Colorado residents: four registered Democrats, four Republicans, and four unaffiliated commissioners. The people chosen can’t be legislators, recent political candidates, party officials, or lobbyists.

That's only $1 per issue!

In the past, state legislators have held most of the responsibility for redistricting. And because these commissions are new, the pressure is on. “You don’t want to come out of these with folks feeling that the process has been unfair,” says former Colorado secretary of state and Democratic state Representative Bernie Buescher, who helped draft Amendments Y and Z. “You want citizens to have confidence in their election processes.”

Here, we broke down everything you need to know about the complicated endeavor, including why it is off to a bit of bumpy start.

I might have fallen asleep during a middle school civics class. Can you explain redistricting for me?

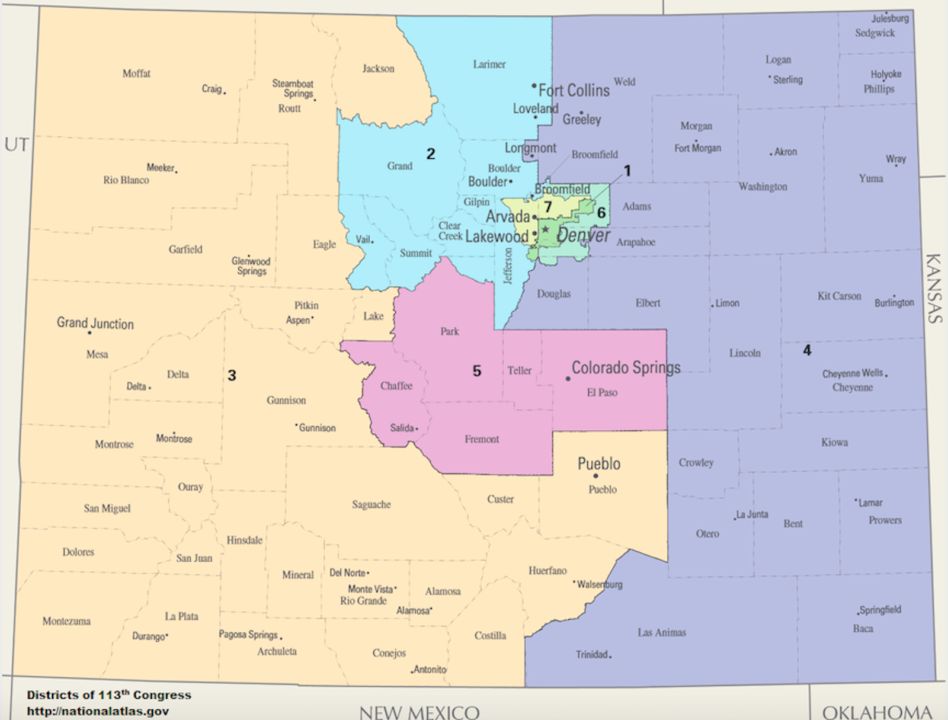

Every 10 years, the U.S. Constitution requires the U.S. Census Bureau to count the nation’s population, and states use the updated demographic information to determine the boundaries for congressional districts. States may lose or gain districts based on how population has changed. (Colorado is expected to get an eighth congressional district this year.) Depending on where the lines are drawn, certain districts might also be more likely to lean Republican or Democratic. Basically, redistricting has a big impact on the composition of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Colorado’s Constitution requires the state to do the same thing for its legislative districts. We’ll still get 35 senate and 65 house districts, but they may look different, depending on where the population has grown and shrunk over the past 10 years.

What was the redistricting process like before?

Until this cycle, the Colorado General Assembly was in charge of congressional redistricting. State legislative redistricting was previously the purview of a “reapportionment” commission appointed by legislators, the governor, and the chief justice of the Colorado Supreme Court. In both cases, elected officials or people handpicked by those groups were charged with drawing the maps that determined the likelihood of their own party holding or gaining seats.

In other words: The process lent itself to partisan power grabs. “In the previous attempts,” Buescher says, “the parties were drafting maps and then jockeying to get significant votes to have those maps adopted.”

Because most states let their legislatures control redistricting, gerrymandering—the practice of purposefully drawing the lines to tilt political power in one party’s favor—is rampant nationwide.

Did Colorado have a bad problem with gerrymandering?

According to Buescher, gerrymandering efforts have not been as egregious in Colorado as in some other states. But that doesn’t mean the last few redistricting efforts haven’t included some nasty fights. In three out of the past four rounds, the legislature was unable to come to an agreement on the congressional map by the set deadline, leaving the final decision up to a district court judge.

That process has often left one party or the other resentful and the map arguably somewhat slanted. The most infamous example is the attempted “Midnight Gerrymander” of 2003, during which Republicans used their majority advantage at the end of a legislative session to pass a new map with boundaries that could have turned six out of seven congressional districts red. The Colorado Supreme Court eventually ruled that map unconstitutional and reinstated the old one.

Democrats have also engaged in some partisan tricks. Rob Witwer, a former state representative who served on the 2011 reapportionment commission as a Republican (he’s now unaffiliated), says the process that year was commandeered by political insiders on both sides, who worked with each party separately on their own maps. After months of debate, Democrats submitted a new map the day before the deadline, without Republicans’ knowledge.

Witwer says that procedural fairness was top of mind when he joined Buescher and a group of bipartisan former legislators to work on redistricting reform. He wanted to see nonpartisan staff draw the first maps in order to avoid an “us versus them” mentality. He also wanted unaffiliated voters to have a meaningful voice in the process.

“[The new system] was really built around the idea that this process needs to be taken out of the shadows,” Witwer says. “There was too much going on in the backrooms, and this is too important of a process not to have more transparency, more public input, and more broad and more diverse representation.”

How are the commissioners supposed to decide how to draw the maps now?

Many of the criteria the commissions are using to create districts are the same as before: They must try to make each district equal in population, and they can’t purposefully dilute any minority group’s influence.

The amended Constitution newly emphasizes the commissions’ responsibility to preserve “communities of interest”—basically, people who share a common concern within the same district. This has always included counties and towns, which are not supposed to be split into different districts unless absolutely necessary, but now it explicitly includes other communities with shared concerns that may be impacted by federal legislation. That could be ties to agriculture or another industry, water needs, educational systems, or racial, ethnic, and language groups.

The second major change is that the commissions are explicitly required to create as many politically competitive districts as possible. Buescher believes that will help ease partisanship and create better legislation. “There is both anecdotal and scholarly data that says that elected officials from competitive districts are forced to listen to all of their constituents, not just their party,” he says.

Who is on the commissions?

A panel of retired judges chose commissioners according to a long, involved process laid out in the revised Constitution. The panel winnowed down applications from interested citizens, looking for people with civic commitment and the ability to be fair and impartial. They also tried to ensure that the commissions reflect Colorado’s geographic, racial, gender, and ethnic diversity.

Congressional Commissioner JulieMarie Shepherd Macklin, a Republican, says she was drawn to the idea that this was an independent process. “Everything in the spirit and design of this really is set up to generate the fairest results possible,” she says.

Already, though, that’s been called into question. In late March, 9News reported that Congressional Commissioner Danny Moore, a Republican whom fellow commissioners had recently elected as chair, had shared Facebook posts in early 2021 supporting unfounded theories that the 2020 presidential election was fraudulent, and repeatedly referred to COVID-19 as the “Chinese Wuhan Virus.”

As calls mounted for his resignation, other commissioners expressed doubts about his ability to distinguish fact from fiction. They even questioned whether his comments would deter Asian-American communities from participating in the process.

“I’m sure everyone on this commission agrees that everyone has the right to freedom of speech,” Commissioner Paula Espinoza, a Democrat, said at a meeting on Monday, April 5. “What is at issue here is Commissioner Moore’s ability to be fair and impartial in his work on this commission and whether he, as chair of the commission, can uphold Colorado citizens’ trust.”

Moore defended his posts and refused to voluntarily resign. Ultimately, the other 11 commissioners voted unanimously to remove Moore as chair. Commissioner Carly Hare, an unaffiliated member of the group, will now head the commission.

How are they actually going to draw these maps?

Nonpartisan staff will draw the first drafts of the maps. Staff Director Jessika Shipley says they will likely start from scratch, focusing solely on meeting the constitutional criteria. “We have to have a report justifying every line we drew. We want to be able to choose the one we can defend the best.”

The commissions are then supposed to get public feedback, holding at least three public hearings in each current congressional district. Staff will then create a new plan and present it to the commission, who can suggest amendments. The commission must have a supermajority, including at least two unaffiliated commissioners, to adopt a plan. If the commission is unable to come to an agreement by the deadline, the third “staff plan” will be submitted to the Colorado Supreme Court for approval.

Isn’t something going on with the Census data?

States were supposed to receive detailed Census data on March 31. But COVID-19 caused delays in data collection and processing, and the Census Bureau says it may not release the information until September 30.

“We absolutely can’t meet any of our deadlines if the data doesn’t come out until September 30, and we still have to take everything on the road,” Shipley says. According to Shipley, the Census also might release some data in early August in a harder-to-process format that staff could crunch. But even then, she says it would be very difficult to meet all the public comment requirements and get a final plan approved by the court by the deadline on November 1.

And extending the deadlines is not a popular option. Candidates who are considering running for election in 2022 need to know what districts they’ll live in and have enough time to file properly and campaign effectively.

The staff may be able to create preliminary plans based on “apportionment data” that will be released by April 30 and will give the total population of the state. They could supplement those numbers with other sources such as the American Community Survey, which collects estimated Census data averaged over the past five years. That would be enough to get them started, and present a preliminary plan to the public, with the caveat that they will tweak details once the real data comes. But there are still legal complications, and neither commission has decided how they will proceed.

So can regular people still be involved in this process?

Yes. While the data delay means the details of local public outreach aren’t sorted out yet, both commissions will be looking for feedback in a variety of ways. They are especially interested in what Coloradans think their communities of interest are. All of the meetings are public and recordings are available online. Any Colorado resident can also submit a public comment at any time in the process via this website.

“It’s my hope that people understand that this is a process that not only can they participate in, but they should participate in, and that it’s not super scary. No matter who you are, you are definitely capable and qualified to give testimony when these commissions come to your town,” says Amanda Gonzalez, the executive director of Colorado Common Cause, a group that works to strengthen democracy and promote public participation.

While the data delays and the scandal surrounding Commissioner Moore have meant a rocky start, many remain hopeful that the process will work as intended and result in fairer maps.

“[The commissioners] have an opportunity to restore public faith in the system,” Witwer says. “And if they’re truly transparent and minimize partisanship and take public testimony to heart… they can help begin the process of restoring faith in our institutions.”