The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals.

The first time I came out West, I fell in love with the land. It was fall break at my university in my native Indiana, and on a whim, I jumped into a car with a couple of buddies who were driving to Colorado to do some hiking. On that trip, I took in the rippled horizon from the summit of Quandary Peak, got chased down a waterfall-dotted trail in Rocky Mountain National Park by a sudden thunderstorm, and drifted off to the sound of elk bugling outside an Estes Park cabin.

The second time I visited, I fell for the people. The wonder Colorado’s scenery had stirred in my flatlander heart compelled me to apply for an internship at this magazine. But when I flew in for the interview, it was the can-do enthusiasm I encountered in conversation after conversation that sold me on starting my career, and the next chapter of my life, here.

Sixteen years later, I feel so lucky to put together our annual “Best of the Mountain West” package, which celebrates both the landscapes and the people that make this region such an exciting place to call home. It’s my hope that the stories here—the nation’s first proposed climate refuge in Montana, an Arizona artist challenging border stereotypes, a climbing mecca in southern Idaho—encourage you to explore the breadth of experiences available to those of us fortunate enough to live here and maybe even inspire you to fulfill your own Western dream. —Jessica LaRusso, editor-in-chief

Jump Ahead:

- Stio Ridgecap Low Shoe, Wyoming

- City of Rocks National Reserve, Idaho

- 53rd Annual Summit for the National Brotherhood of Snowsports, Colorado

- Lehman Caves, Nevada

- Jaelin Kauf, Wyoming

- Infinite Outdoors’ Access Granted Program, Wyoming

- Martiny Saddle Co., Idaho

- Until Forever Comes: This is Ute Homeland, Colorado

- Alejandro Macias, Arizona

- Moab Music Festival, Utah

- The Incline Lodge, Nevada

- Route 66, New Mexico

- Begin Where You Are: The Colorado Poets Laureate Anthology, Colorado

- Tucson Folk Festival, Arizona

- Stephanie Land, Montana

- Black Desert Resort, Utah

- “Seven Magic Mountains,” Nevada

- The Sylvan Lodge, Wyoming

- Black Ram Climate Refuge, Montana

- Meriwether Cider, Idaho

- Los Poblanos Historic Inn & Organic Farm, New Mexico

- Lom Wong, Arizona

- Bidii Baby Foods, New Mexico

- Old Salt Co-op, Montana

5280 Best of the Mountain West 2025: Adventure

Stio Ridgecap Low Shoe (Men’s and Women’s), Wyoming

“Trail-to-town” is the outdoor industry’s version of fake news, so consider us pleasantly surprised by this slick sneaker’s technical chops. A first foray into hiking footwear from Jackson-based mountain lifestyle brand Stio (which has outposts in Steamboat Springs, Vail, and Breckenridge and on Pearl Street in Boulder), the Ridgecap Low (available in men’s and women’s) shows its stuff on dry Front Range trails. A Vibram Megagrip outsole clings to slickrock, while shallow, chevron-shaped lugs help you toe off or brake on looser paths. The ride is plush, like a trail-running shoe, and a hidden rock plate under the ball of the foot keeps the shoe from collapsing on off-kilter terrain.

That nice-looking exterior is sneaky technical too: A breathable nylon mesh keeps tootsies cool, while suede and nubuck overlays keep the foot secure and help the Ridgecap pass as officewear. At $159, the Ridgecap Low costs less than what similar shoes were going for a decade ago, and more impressively, the Ridgecap Waterproof Mid—a higher-cut boot with a waterproof membrane—is $189 (also available in men’s and women’s). Should you want to push a shoe into winter or wear it backpacking, you can’t do much better. And no one will look twice when you pull up to après. —Maren Horjus

Read More: Boulder’s Pearl Street Has Become the Rodeo Drive of Outdoor Apparel

City of Rocks National Reserve, Idaho

When the forces of wind and water went to work on the billion-year-old granite at this federally protected southern Idaho park, they didn’t just sculpt a gorgeous landscape of arches, caves, and spires. They also crafted the rocky cracks, knobs, and slabs that have made the City a paradise for climbers. More than 600 sport and trad routes—most of them in the moderate 5.10 to 5.11 range, but with easier and tougher options, too—attract aspiring Spider-Mans of all ages. “It’s known for being fun for the whole climbing family,” says Erik Leidecker, co-owner of Sawtooth Mountain Guides. “Kids love it because the landscape is just like a playground.”

Besides scaling rocks, travelers come for mountain biking, hiking, birding (179 species wing through the park), and history (the names of California Trail emigrants decorate some rocks). Staying overnight in one of the reserve’s superb car campsites is mandatory: In this far-flung spot, the entire galaxy blazes before your eyes. —Elisabeth Kwak-Hefferan

53rd Annual Summit for the National Brotherhood of Snowsports, Colorado

The Annual Summit for the National Brotherhood of Snowsports is a fundraiser. But it feels more like a family reunion, NBS president Henri Rivers says of the more than 1,500 people who hit the slopes during the United States’ largest gathering of Black snowsports enthusiasts. This February 28 to March 7, the good vibes will once again descend on Keystone Resort, marking the first time in NBS history that the summit, in its 53rd year, has returned to the same ski area for consecutive years.

Keystone’s trio of distinct peaks and 3,149 skiable acres—which provide ample beginner terrain, in line with NBS’ mission to increase participation in winter sports—certainly affected the decision to return. It was the hospitality offered by parent company Vail Resorts, Rivers says, that truly drove the homecoming to Keystone: “From ski patrol to lift ops to operations and hospitality, their staff treats us well. Their arms are open.” —Courtney Holden

Read More: The National Brotherhood of Skiers Is Cultivating Black Snowsports Stars in Colorado

Lehman Caves, Nevada

If you’ve been caving, you’ve likely been told not to touch the walls in order to protect the fragile environment. But back in the 1920s, when tourism inside eastern Nevada’s Lehman Caves was in its infancy, private owners would do just about anything to attract visitors, including hosting weddings and large group meetings in the underground chambers. Guides would even play music by striking the stalactites and stalagmites with hammers. “Such entertainments decreased as formations broke under the constant pounding,” wrote Keith A. Trexler in Lehman Caves…Its Human Story.

Today, visitors who explore the cave network during year-round, ranger-led tours—the only way to enter Lehman Caves—are handed lamps, not mallets. Guides lead groups of 20 through 0.3 mile of chambers on the Gothic Palace Lantern Tour or up to 0.6 mile on the Parachute Shield Tour. Plan your trip for late spring 2026 or beyond, when the caves will reopen following a closure to install a new electrical lighting system. The updated tech will help spelunkers see Lehman Caves’ more than 500 shield formations (two parallel calcite plates), Gypsum flowers (flora-like crystals), and Great Basin pseudoscorpions (small arachnids with two large pincers). Just remember to keep your appendages to yourself. —Jessica Giles

Jaelin Kauf, Wyoming

When Jaelin Kauf skis up to the start line and sets off down a bump-covered white blanket, she doesn’t have speed on her mind. “I don’t try to be the fastest, necessarily,” says the 2026 Team U.S.A. member. But with a silver medal from the 2022 Games, 16 Freestyle World Cup victories, and a FIS Freestyle World Ski Championships gold medal to her name, it’s clear things often work out that way.

Hailing from Alta, Wyoming, Kauf will test her velocity—not to mention her turn technique and two jump tricks, the other elements scored in her mogul and dual mogul events—this February on the Olympic slopes in Milano Cortina. But even there, Kauf, who races with her mantra “Deliver the Love” emblazoned on the back of her helmet, won’t let her thirst for a place on the podium interfere with her mission to spread goodwill and stoke to women and girls: She partners with the Women’s Sports Foundation, which advocates for women’s and girls’ opportunities in sports.

“It’s easy to get caught up in results,” she says, “but at the end of the day, I want to ski and live from a place of love and passion.” —CH

Infinite Outdoors’ Access Granted Program, Wyoming

The West takes great pride in its vast open spaces. But nearly 16 million acres of local, state, and federal lands across the region—including 704,000 acres in Colorado—are landlocked, meaning they’re surrounded by private property and thus inaccessible to the public, despite the fact that, as the song goes, this land is our land. Enter Infinite Outdoors. Since 2020, the platform (based in Casper, Wyoming) has connected recreationists with opportunities to hunt, fish, and camp on private lands.

That effort expanded greatly in the spring with the introduction of its Access Granted program, which specifically focuses on opening pathways to landlocked public areas. So far, the effort has granted entrée to more than 50,000 acres and a half-dozen miles of water in Colorado, Montana, and Wyoming. While use of the app and website to connect with these sites is free, a $50 annual membership adds the ability to reserve private land access, among other perks. “The intent,” says co-founder Sam Seeton, who grew up on a ranch near Buena Vista, “is to help everybody just get outside and explore public lands.” —Daliah Singer

Read More: What the New EXPLORE Act Will Mean for Coloradans

5280 Best of the Mountain West 2025: Culture

Martiny Saddle Co., Idaho

In the high mountain desert of eastern Idaho’s Pahsimeroi Valley, Nancy Martiny builds some of the West’s most sought-after saddles. The 66-year-old lifelong cowgirl, whose one-woman Martiny Saddle Co. operates out of a cabin on her husband’s family homestead, has been building heirloom-grade pieces for 35 years. Her distinctive creations are adorned with elaborate floral patterns carved petal by petal in looping arrangements. Fewer than a dozen leave Martiny’s workshop each year, and each is hand-drawn and hand-tooled.

Martiny learned leatherwork from her father as a teenager and saddle-building from industry legend Dale Harwood, though she’s often her own best advertisement: Martiny and her husband operate a working ranch, and she rides in the same saddles she sells. “I need to have hands-on use so I can understand how it needs to function, beyond just what’s pretty,” she says. Prices start at $6,000 and can climb to $15,000 for fully flowered showpieces. The waitlist is currently six years long, and Martiny has no plans to collect new commissions. (She once declined an elderly client because he’d be dead before he got his order.)

For the rest of us greenhorns too late for a saddle, Martiny has an assortment of headstalls, halters, purses, and notebook covers available for purchase on her website. —Robert Sanchez

Until Forever Comes: This is Ute Homeland, Colorado

The Nuuchiu (Ute people) do not have a migration story. “We’ve always been here,” says Crystal Rizzo, cultural preservation director of the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, referring to the oral tradition that Sinawav the Creator placed her people directly in the Rocky Mountains. “We’re still here.” That legacy now takes center stage at the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum in Until Forever Comes: This is Ute Homeland.

The permanent exhibition (a five-year collaboration between the free museum downtown and the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, and Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation) features photography, language preservation and revitalization, and historical artifacts alongside contemporary works—vibrant ribbon dresses and shawls, buckskin moccasins, and hand-crafted beadwork—from more than 24 Ute artists. “We’re rich in our history, our culture, and our language, and I really want people to be able to see that,” Rizzo says of the exhibition. “This is us telling our story.” —CH

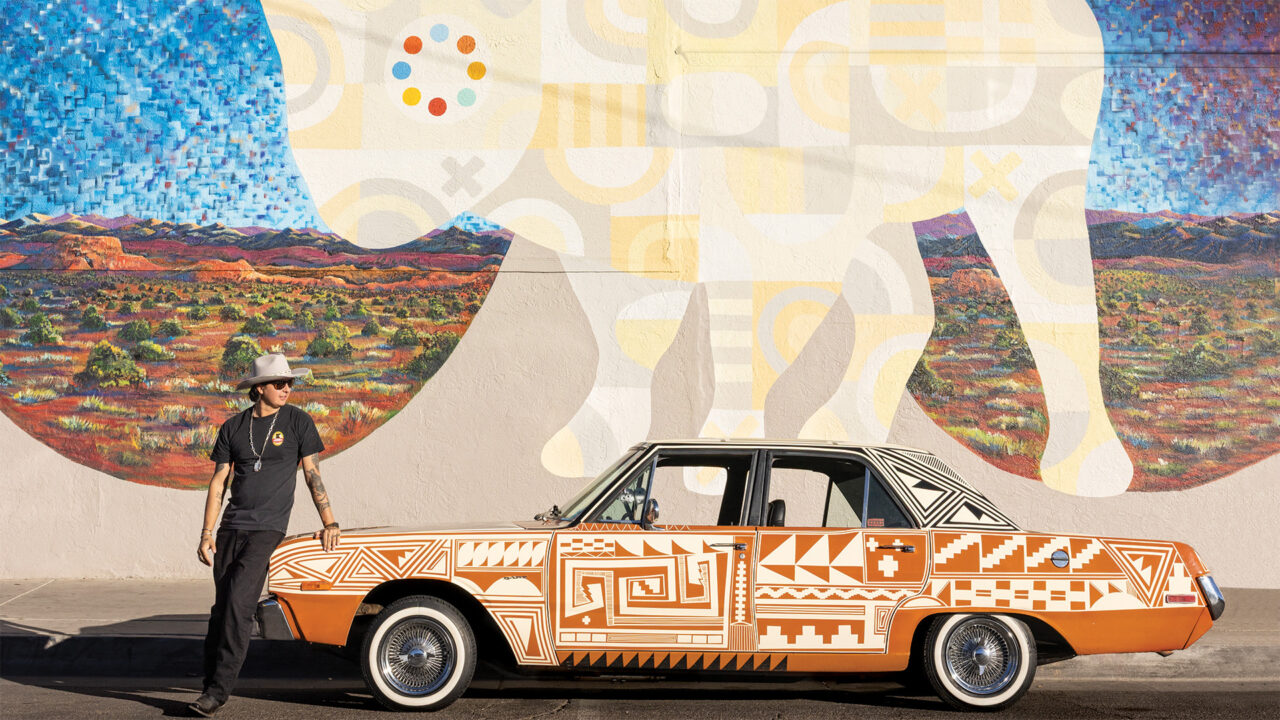

Alejandro Macias, Arizona

Brightly colored serapes—traditional Mexican blankets with stripes—feature prominently in Alejandro Macias’ work. In an ongoing series of oil and acrylic paintings, the 38-year-old Tucson-based artist depicts Mexican-American men commonly seen around Brownsville, his South Texas hometown: a uniformed Border Patrol officer; a man in a San Antonio Spurs T-shirt; a Trump voter with a red MAGA cap. Their faces are often obscured by the serape’s stripes, evoking both assimilation and pride. The portraits are playful but also overtly political—a duality that pervades Macias’ art, which extends to graphite, video, and collage.

With immigrants under attack, he feels an urgency to push back against stereotypes. “If I can ignite some sense of hope, if I can help someone perceive the border differently, then I’m doing something correctly,” says Macias, who’s also an associate professor of art at the University of Arizona. Catch his work at the Tucson Desert Art Museum through June 27, 2026, and at Albuquerque’s 516 Arts through January 31, 2026. —Rose Cahalan

Moab Music Festival, Utah

A piano staged on the dirt floor of a wilderness grotto only reachable by boat; the lilting sound of a string quartet in the shadow of towering red rock formations; riverbank concerts that become the soundtrack for a four-day whitewater rafting adventure through Canyonlands National Park. These are just a few of the soul-stirring scenes attendees can enjoy during the Moab Music Festival, which for 33 years has been showcasing a spectrum of musical genres, from classical and jazz to blues and folk, all set in the surreal landscape of Moab’s rocky castles and painted skies. The 2026 festival (from September 2 to 18) will explore the origins of American music alongside our country’s 250th birthday.

A bigger storyline to follow in the festival’s near future? How the evolving landscape—thanks, climate change—will alter the course of the festival’s traditions. “We were crossing our fingers just this past season that the Colorado River would have enough water to get a piano down it,” artistic director Tessa Lark (pictured) says. “We just don’t know how long we will be able to enjoy these awesome—in the biblical sense of the word—landscapes.” In other words: Don’t sleep on securing your 2026 tickets. —Julie Dugdale

The Incline Lodge, Nevada

At this two-year-old mountain-modern hotel on the northeastern shore of Lake Tahoe, what’s outside is every bit as important as what’s under its roof. Diamond Peak Ski Resort (a free shuttle provides door-to-door service); the scenic Tahoe East Shore hiking and biking trail; an 18-hole public golf course; and three private swim beaches (one with a heated pool) are all within minutes. When you’re finally ready to head indoors, the Incline Village spot welcomes guests with a fireplace in the lobby, live music in the cozy Après Lounge & Bar, and sleek rooms decorated with old-school snowshoes and vintage skis.

It all began when University of Colorado Boulder alum Ali Warner and his wife, Natasha, bought an outdated motel down the street from their house in 2022. After a yearlong renovation, they reopened the Incline Lodge (starting at $200 per night) to international accolades, notching runner-up honors in the hotel-design-focused Gold Key Awards. Next, the lodge is preparing to launch an in-house activity menu that makes it even easier for guests to get out and explore, from downhill mountain bike rides to chickadee-feeding excursions in an alpine meadow. —EKH

Route 66, New Mexico

Historic Route 66, which traverses 2,400 miles across eight states, including New Mexico and Arizona, was established in November 1926 as one of the country’s first highways. A key thoroughfare during the Depression for people headed West to seek work and better circumstances (and during and after World War II), Route 66 encapsulated the American dream: Enterprising residents in small, previously overlooked towns established motels, diners, and gas stations along the route.

Though it was decommissioned in 1985 in favor of newer interstates, the roadway—and its ubiquitous neon signs—remains a bucket-list road trip for many. “It’s a celebration of the spirit that built the American West,” says Brenna Moore, Visit Albuquerque’s director of communications and public relations. The city—which claims “the longest continuous urban stretch [18 miles] of the Mother Road” and the only place where the original (through Santa Fe) and new highway alignments cross each other—has already kicked off its Route 66 centennial celebrations. Be sure to pull over along Albuquerque’s Central Avenue to take in 18 large-scale art installations, murals, and digital features, all by local creatives. —DS

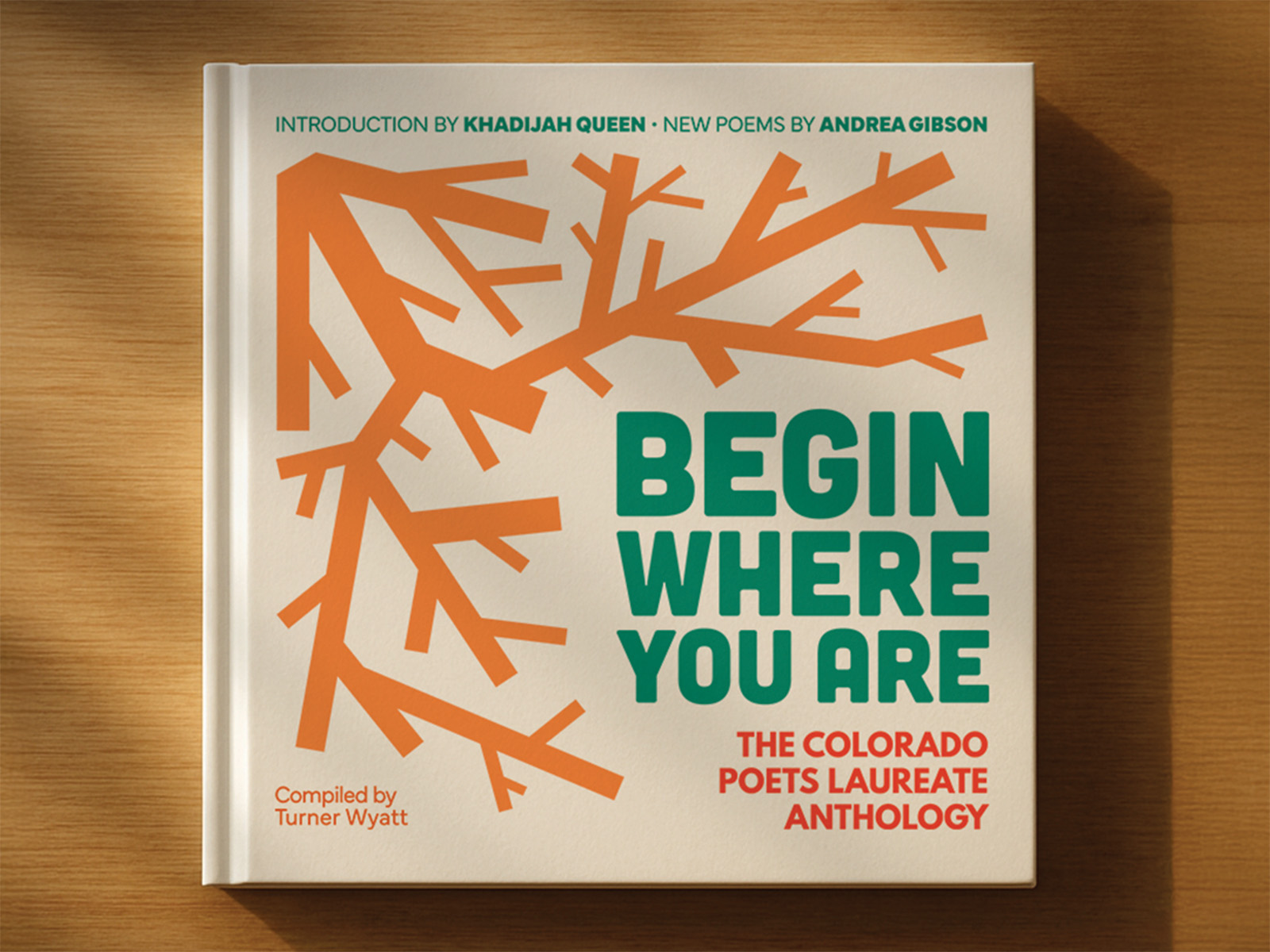

Begin Where You Are: The Colorado Poets Laureate Anthology, Colorado

In 1919, Colorado became the second state (after California) to establish a poet laureate program, but the work of these luminaries has never been gathered into a single collection—until now. The first-of-its-kind Begin Where You Are: The Colorado Poets Laureate Anthology will be published by the Center for Literary Publishing and distributed by the University Press of Colorado this month. The book features verse from a century of Centennial State poets, from Alice Polk Hill to Bobby LeFebre. It also includes previously unpublished work from Andrea Gibson, a much-lauded queer, nonbinary spoken-word poet who served on the editorial committee and died after a long illness this past July. In the introduction to their work, Gibson celebrates Colorado poets, who they say taught them how to trust their voice, tell the truth, and, above all, “that being a poet isn’t so much about how we show up to the page but how we show up to the world.”

Proceeds from the book will support poetry programs in underserved areas of Colorado. —Kate Siber

Read More: 9 Questions With Colorado’s New Poet Laureate

Tucson Folk Festival, Arizona

Fans of folk music don’t forgive those who betray the genre: Even Bob Dylan got booed when he went electric at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. To ensure such a travesty never transpired on their stages, the founders of the Tucson Folk Festival put it in writing—no electric guitars!—when they launched their event 40 years ago. Arizona’s largest free music festival soon earned a reputation as a laid-back jam session. “Someone plays with you out by a tree, and they’re like, ‘Come join me in my set,’ ” says Matt Rolland, formerly of the folk quartet Run, Boy, Run.

But the times, they’ve changed. Board president of the Tucson Folk Festival since 2020, Rolland also serves as deputy director of the nonprofit Art State Arizona. He spearheaded a partnership between the two organizations, giving the three-day festival (April 10 to 12 this year) some needed stability. Under the alliance, organizers also loosened their strings on what constitutes folk. The six stages, spread across three blocks of downtown Tucson, now include mariachi, zydeco, and tunes from the nearby Tohono O’odham Nation. Electric guitars can even be heard reverberating through the streets—and attendance has increased by 40 percent over the past four years. —Spencer Campbell

Stephanie Land, Montana

Amid the chaos of our current political discourse, Stephanie Land’s writing hits like a gut punch. In her bestselling memoir, Maid (2019), and its 2023 follow-up, Class, Land deftly used her experiences as a single mom struggling with homelessness and poverty to expose the gaping holes in society’s safety net. Her upcoming third book, The Privilege to Feel, takes on the emotional toll of inequality. The in-progress essay collection spans 30 years, examining everything from a medical emergency that bankrupted her in her early 20s to surviving an abusive partner to enduring a series of miscarriages.

“Being able to process the events that happen in our lives is a very privileged act, to find the space and time and resources to really sit with those feelings,” says the author, who is based in Missoula, Montana. Can’t wait for more? Pick up The Shelter Within, an e-book released this year that Land considers the missing final chapter of Class. —EKH

Black Desert Resort, Utah

Spread across 600 scrub-brushed acres backed by vermilion cliffs, Black Desert Resort—particularly, the brilliant greens of its golf course, which winds through lava fields—looks like a mirage. But the luxurious property, which launched its preview phase in the southwestern Utah town of Ivins in fall 2024, is very real. With construction on the resort’s 447 rooms and suites and amenities (an infinity-edge pool ringed by cabanas and fire pits, seven food and beverage options, the 15,000-square-foot Plume Spa & Wellness Center, and that Tom Weiskopf–designed, championship-grade golf course) finally finished in September, it’s now a destination-worthy oasis.

Black Desert Resort (from $383 per night) has already hosted events on both the PGA and LPGA tours, but there’s plenty to entertain visitors who prefer footpaths to cart paths: In addition to six miles of on-property hiking trails, Snow Canyon State Park is a couple of miles up the road and Zion National Park is just a daytrip away. —JL

“Seven Magic Mountains,” Nevada

Just south of Las Vegas, Swiss artist Ugo Rondinone’s “Seven Magic Mountains” rises from the Mojave Desert: seven 30-foot columns of massive, vibrantly hued stacked boulders that fuse nature’s vastness with the playfulness of the human imagination. Originally erected in 2016 and intended as a temporary installation, the piece—made of real stones and Day-Glo pigments—has defied its expiration date, remaining on view thanks to immense public affection (and a few Bureau of Land Management extensions). A planned relocation to northern Nevada was called off earlier this year because the Nevada Museum of Art was unable to secure a site, meaning visitors have until at least 2027 to bask in its surreal fluorescence less than a half hour from the Strip. —Malia Logan

The Sylvan Lodge, Wyoming

For nearly 20 years, Jackson’s Snake River Sporting Club has been an exclusive alpine setting (and working ranch), with 1,000 acres of pristine wilderness and one of the state’s top golf courses accessible only to residents and members. That changed in June with the opening of the Sylvan Lodge. The 38 contemporary, wood-bedecked rooms and suites (starting at $449 per night) are outfitted with oversize windows and heated bathroom floors.

But it’s what’s outside the front door that makes Sylvan worth your hard-earned dollars: Set along the Snake River and Bridger-Teton National Forest, the retreat gives guests temporary club membership, opening up seven miles of private fly-fishing, cross-country skiing and hiking trails, platform tennis courts, and an outdoor ice rink as well as add-on experiences like spa services, horseback riding, and heli-skiing. When night falls, it’s time to head to the on-site Dark Sky Bar. In the spring, Teton County became the world’s first county to be named an International Dark Sky Community. With six west-facing, outdoor hot tubs, the fireplace-laden rooftop terrace is the perfect place to see the stars—with a bourbon-forward Big Dipper cocktail in hand. —DS

Black Ram Climate Refuge, Montana

In the northwest corner of Montana lies the Yaak Valley, a haven of unusually rich biodiversity. Due to a collision of weather patterns that creates climate resilience, the old-growth forest here thrives as a major carbon storage hub and harbors 25 percent of Montana’s sensitive species. In fact, it’s one of only six grizzly bear recovery areas in the lower 48 states. “It’s not like any other ecosystem in the world,” says Rick Bass, executive director of the Yaak Valley Forest Council.

The council recently fended off the controversial Black Ram logging proposal, which would have decimated thousands of acres of forest in the Yaak. Instead, the group, supported by recent scientific findings published in the academic journal Forests, is calling for federal authorities to designate the Yaak as the nation’s first official climate refuge. This would put protections in place to preserve its undisturbed forests, soils, and ecosystems. “There’s a lot to learn about this place, scientifically,” Bass says. “It’s also a real incubator for artists who are moved by the mysterious character and quality of the valley. It has so much hope for us amidst so much climate grief. The opportunity to protect it now lies before us, waiting.” —JD

5280 Best of the Mountain West 2025: Eat & Drink

Meriwether Cider, Idaho

Just about everyone knows what sommeliers are. Suds-loving Coloradans are likely to have heard about cicerones, the rigorously trained beer equivalent. But a pommelier? “It’s the highest level of cider certification you can have in this country,” says Molly Leadbetter, the owner of Meriwether Cider, an urban cidery with taprooms in Boise and nearby Garden City. Last year, she became one of fewer than 150 American Cider Association–certified pommeliers in the world—and the first in Idaho—by demonstrating her expertise on everything from orchard management to juicing and fermentation to food-and-cider pairings to sensory analysis (the sniffing and swirling part). “A lot of it for me was about giving more credibility to the entire state,” Leadbetter says. “Being like, yes, Idaho has good cider.”

Some of the most celebrated are Meriwether’s flagships, which include the “big, bold, fruity” Black Currant Crush; the Foothills Semi-Dry, which Leadbetter describes as Prosecco-esque; and the 8.5 percent ABV Uncharted made with oak tannins. But as part of her mission to uplift the entire scene, Leadbetter also founded the Idaho Cider Fest, which will hold its fourth annual event on October 3, 2026, and showcase more than a dozen Western cideries. —JL

Los Poblanos Historic Inn & Organic Farm, New Mexico

Whether you’re visiting the peaceful grounds of Los Poblanos in Los Ranchos de Albuquerque for a wedding, spa treatment, or dinner at its nationally lauded restaurant, Campo, you’ll remember the sights, aromas, and flavors—lavender, herbs, corn, and peppers, all grown on-site—long after you return home. Fortunately, a well-stocked farm shop on the property (and on its website) offers an array of honey, preserves, baking mixes, and other specialty items that allow you to bring a taste of the 26-year-old inn and its nearly century-old farm to your kitchen.

Our favorite: a salt blend cheekily named Better Call Sal, which combines the essence of Italian truffles with Los Poblanos–grown oregano. It’s delightful sprinkled on scrambled eggs or as a rub for roast chicken. Better yet, order a four-pack sampler that includes three other salts: Oaxacan, toasty with imported chilaca chiles; Woodfire, smoked with local hardwood; and Chimayó, vibrant with New Mexico’s legendary chile grown in its namesake pueblo. —Mark Antonation

Lom Wong, Arizona

Yotaka “Sunny” Martin, co-owner of Thai eatery Lom Wong in Phoenix, won the James Beard Foundation’s Best Chef: Southwest this year, but she says the award belongs to the restaurant as a whole, especially since her husband, Alex, is an equal culinary and business partner. In fact, being considered “chef-driven” is the exact opposite of what the Martins have aimed for since they began hosting pop-up dinners in their living room in 2019.

The menu at Lom Wong, which opened in a converted Evans Churchill bungalow in 2022, comprises dishes from Sanmaket, where Yotaka was born and raised; Tahm Phratat, where Alex learned to cook meals from a woman he calls his adoptive Thai grandmother; and Taptawan, where the Indigenous Moklen people taught him their foodways over the course of his dozen years living in Thailand. Makrut lime leaves for the Moklen pork belly curry come from Thai farmers near Phoenix, and Yotaka’s mom regularly sends ingredients like laap spice mix from the family farm in Thailand. “We put a lot of our hearts and ourselves into it,” Yotaka says of the Lom Wong team. “Come into our restaurant with that open heart as well.”

To best follow that advice, tell your server “arai kodai” (“I’m down for whatever”) to experience a meal the way they do it in Thailand: “sitting together in a circle,” as the name Lom Wong means. —MA

Bidii Baby Foods, New Mexico

Zachariah Ben represents the sixth generation of his family to farm 16 acres of arid land on the Navajo Nation in northern New Mexico. In 2021, the Diné (aka Navajo) farmer and his wife, Mary, launched agricultural co-op Bidii Baby Foods to ensure even the tiniest tribal members can connect to their culture’s culinary heritage. Using ancestral regenerative and organic practices, the pair cultivate white and yellow Navajo corn along the banks of the San Juan River; after harvest, the ears are steamed and dehydrated, and the kernels are ground into neeshjhizhii, a dry cornmeal caregivers can boil to make a traditional soft baby food. The product is shelf stable, an essential attribute for the 30 percent of Navajo Nation residents who live without electricity or running water.

The Bens don’t stop nurturing Diné youth once they start on solids, however: Their Farmer-in-REZidence incubator program supports and mentors the next generation of young Indigenous entrepreneurs who want to establish agricultural businesses on tribal land. —Amy Antonation

Old Salt Co-op, Montana

Cole Mannix’s family practiced regenerative techniques dedicated to soil, water, and ecosystem health on their mountain-rimmed property in Montana’s Blackfoot Valley for generations. But the conventional American agriculture industry that prizes bottom-scraping prices over land stewardship makes living their values nearly impossible. So Mannix decided to build his own system. Old Salt Co-op, a coalition of regenerative cattle producers across the state—plus its own processing facility and direct-to-consumer meat business—launched in 2021.

But that was just the start. Old Salt also opened a pair of Helena restaurants to showcase its meat: a smashburger joint called Old Salt Outpost and the Union, a classy, wood-fired grill that snagged a James Beard nomination for best new restaurant this year. And every June, thousands gather on the Mannix family ranch for the Old Salt Festival, a delicious combo of Americana concert, sustainable-ag conference, and open-fire foodie gala.

“The difference in what’s not working now and what we’re hoping to move toward is the difference between an industrial process and a living system,” Mannix says. “I think it’s a better future for my kids to grow up in.” —EKH