The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals. Sign up today!

Update, 9/27/19: Ashley Kilroy, director of Excise and Licenses, approved the liquor license and dance cabaret license for the Yates Theater, stating in the decision that she “finds no factual or legal grounds to reject the hearing officer’s findings or conclusions.”

Update, 6/24/19: Hearing Officer Kim Chandler recommended the Department of Excise and License approve the license applications for the Yates Theater. Her recommendation will be reviewed by Excise and License Director Ashley Kilroy, who will then render a final decision.

That's only $1 per issue!

On June 13, room 206 of the Wellington E. Webb Municipal Office Building had a peculiar buzz for a summer evening. A liquor and cabaret license hearing was set to take place, which might sound like a mundane, easy-to-clear bureaucratic hurdle. But even 30 minutes before the hearing began, an empty seat was hard to find. Some attendees wore green badges that read: “No Need. No Desire. No License.” About half of those in the room also wore red shirts, a show of solidarity against the evening’s proposal.

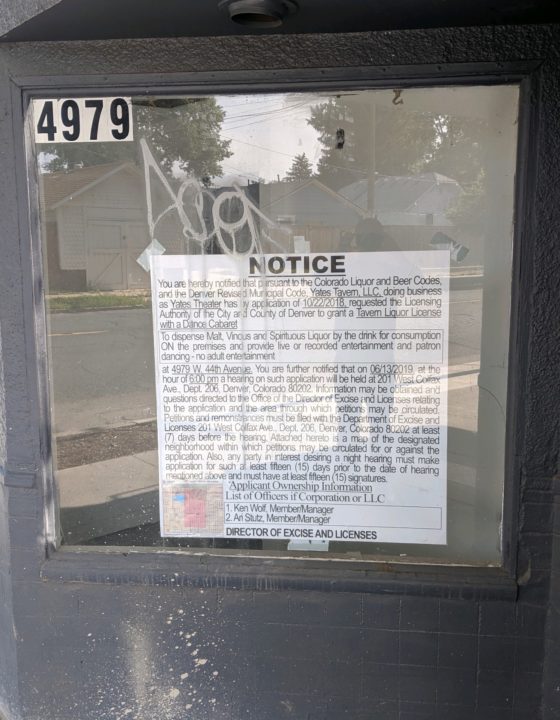

At one end of the hearing table sat Ari Stutz, a developer trying to reopen Yates Theater, a historic building on 44th Avenue in the Berkeley neighborhood that has been vacant for many years. Across from him sat Chris Gaddis from the City Attorney’s Office. To his left was Kim Chandler, the hearing officer. To his right was a crowd of attentive Berkeley residents.

For Stutz, the hearing was crucial.

“This is going to be a $1.5 million to $2 million dollar investment,” he said during testimony. “We wouldn’t build it out without being able to run this business, which is pretty predicated on having this liquor license.”

Stutz’s team, which includes developer Ken Wolf and longtime restaurant operator Jerri Theil, envisions a mixed-use space that will serve as a music venue and theater, and when no performance is scheduled, a neighborhood bar. In order to operate such a concept, the developers need a cabaret license—which allows them to host live entertainment—in addition to the liquor license. For the neighborhood residents who oppose the idea, particularly those in closest proximity to the theater who worry about crowds as large as 700, parking limits, and noise, blocking those licenses is one of the surest ways to sink the development.

Taylor Hart-Bowlan, an attorney by trade who lives only 60 yards from the theater, served as a party of interest for those opposed at the licensing hearing. She doesn’t see the licensing process as the absolute last opportunity to block the project, but she agrees it’s one of the more effective means of recourse.

“In many ways,” Hart-Bowlan says, “the liquor license can be a straight-to-the-jugular approach.”

The group opposed to the theater is nearly equal in official number to those who support the development. When petitions were counted at the hearing, 291 signatures were submitted by the opposition, compared to 311 by those in support.

However, blocking a liquor or cabaret license in Denver is no simple task. According to Eric Escudero, director of communications for the Department of Excise and License, out of more than 500 applications, the city has only denied three liquor licenses in the past year—and all of those were denied because of proximity (an establishment serving alcohol can’t be within 500 feet of a school, for instance). As for cabaret licenses, Escudero says the city has received 12 applications this year; one was approved, one was denied, and 10 are still pending.

Making matters even more complicated, Stutz already secured a good neighbor agreement (GNA) with Berkeley Regis United Neighbors (BRUN), the registered neighborhood organization that officially represents those living in the surrounding community. While a GNA is not required and is difficult to enforce, it shows that the developer engaged the community in conversation before applying for licenses—which bodes well for Stutz’s application. The GNA for the Yates Theater, for instance, stipulates live music would end by 11 p.m. Sunday through Wednesday, by midnight on Thursdays, and by 1:30 a.m. on weekends. The GNA also addresses issues like parking capacity, noise level, and security.

Still, some residents argue the agreement falls short, particularly because there wasn’t enough neighborhood input and it doesn’t take into account the interests of all neighbors. Hart-Bowlan, for instance, is not confident the theater operators will be able to manage parking or noise, and she doesn’t think the GNA outlines effective solutions on either front.

Denver liquor licenses are rarely denied, but the folks in opposition to Stutz’s project have already accomplished something rare. The vast majority of licensing hearings are held during regular business hours, and only in special circumstances—like vast public outcry—will hearings be held in the evening. According to Escudero, out of 109 needs and desires hearings held by the Department of Excise and Licenses in 2019, the Yates Theater is the only case that required a night hearing—and it lasted about five hours before wrapping up at 11 p.m.

According to Marley Bordovsky, director of prosecution and code enforcement for the City Attorney’s Office, only two or three cases each year—of several hundred—see such high level of community engagement during the hearings. She also noted it’s unusual for there to be such robust opposition in a case where a GNA was already signed by an applicant and neighborhood organization.

All of these factors—the GNA, the opposition, and the strength of application—will be considered as the Department of Excise and License works toward a decision on Yates Theater, but exactly when that decision will be announced is unclear. The hearing officer will first make a recommendation to Ashley Kilroy, the department’s executive director, who will then seek out additional community input before deciding whether or not to grant Stutz and his team the licenses.

According to Escudero, there is no firm timeline for this process. The department will try to reach a decision in a timely manner but, he says, “We’d rather get it right than fast.”