The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals. Sign up today!

In this Weird Year, there are people I have needed to hear from again for the sake of my sanity. My two favorites are gone: Anthony Bourdain and Christopher Hitchens. Neither man had patience for injustice or idiocy. Given 2020’s unceasing injustice and idiocy, I’ve been rereading and re-watching both Tony and Hitch.

I was blessed to see Hitchens, the British-born social and political critic, in person in Alabama in 2010 at a Christian think tank debate about atheism. He struggled to the podium, bald and weary from chemo, and I feared a diminished roar from the great lion. Oh, me of little faith! He was learned, sharp, and funny. We infinitesimal creatures, he said, are made of dust from the stars of a billion billion galaxies, and as we will go the way of all stars, the original sin is to not think critically in our brief meantimes. Witnessing his brain at work, as he faced his own extinction, was nourishing. When Hitchens died the following year, Bourdain tweeted: “The world just got a helluva lot dumber.”

Bourdain, whose 2018 death by suicide was one helluva shock, offered us the same kind of succor as we watched him tramp and puzzle and exult his way through life, food, culture, and the world. He led with a mighty heart. What impressed me most was his habit of introspection and his interest in the troubles and labors of others.

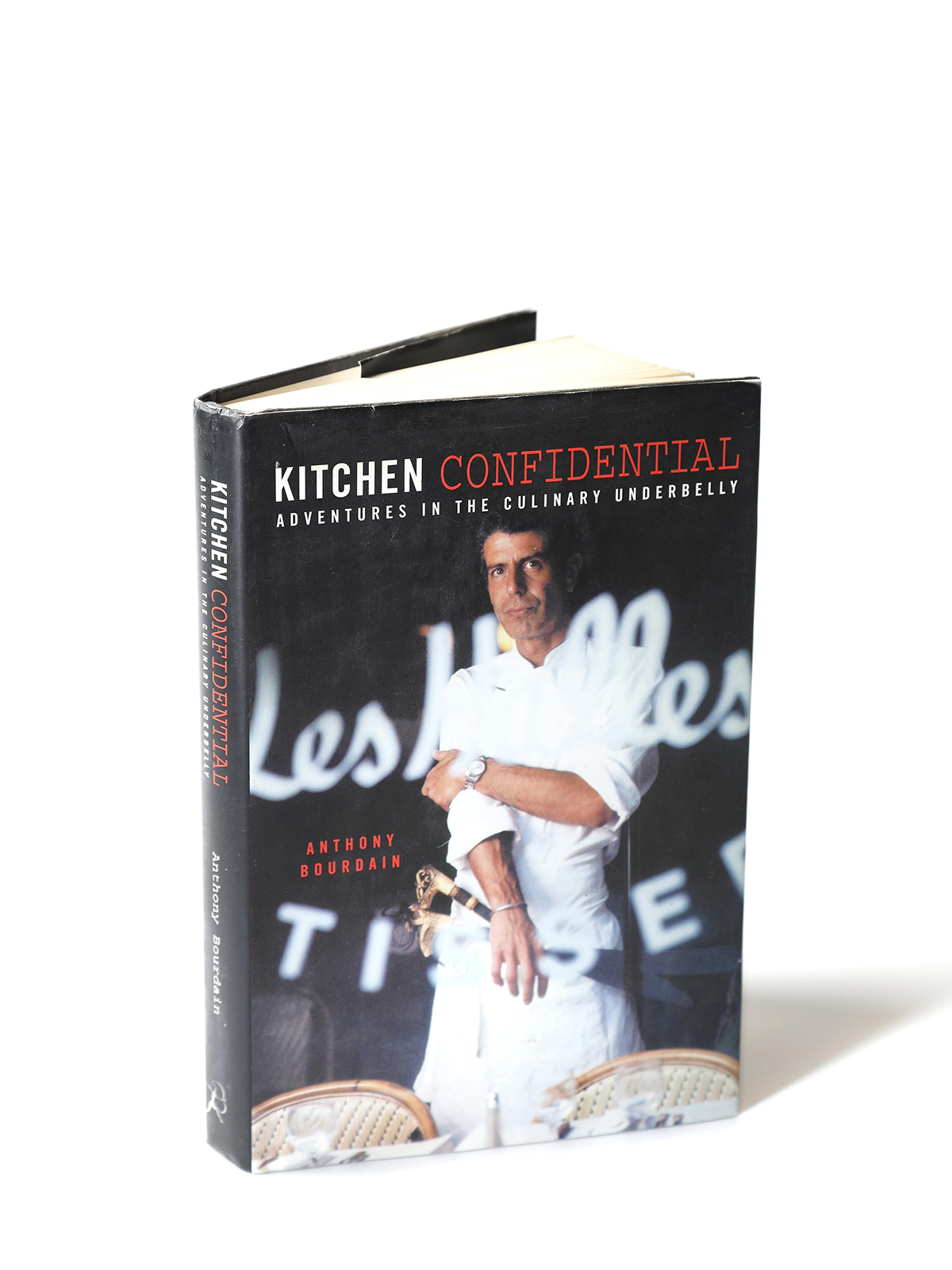

We could use a lot more of that right now, surely. I recently reread Bourdain’s breakthrough book, Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly, on the occasion of its 20th anniversary; it’s worth another read. In 2000, Kitchen Confidential landed like a frozen turkey in a fry barrel, exploding with its dishy accounts of sex, drugs, and criminality in the hothouse journeymen kitchens of New York City. It was fun to read, if a bit oversalted.

By 2017, Bourdain regretted the misogyny and sexism built into the macho bravado of his kitchens, but two deeper themes stand out in Kitchen Confidential. The first was his honesty about two decades of dissolute underachieving (before he got to Brasserie Les Halles, the Park Avenue South bistro where it all came together for him), described with the rare confessional quality that also likely saved him from the worst seductions of fame.

The second was Bourdain’s call to give credit to others. In the case of Manhattan kitchens, that meant mostly underrecognized people of color. Bourdain admired not just the diligence of the “Ecuadorian, Mexican, Dominican, and Salvadorian cooks” who kept those restaurants running, but also their mastery. “A guy who’s come up through the ranks, who knows every station, every recipe, every corner of the restaurant and who has learned, first and foremost, your system above all others is likely to be more valuable…than some bed-wetting white boy whose mom brought him up thinking the world owed him a living,” Bourdain wrote.

He thus fired an early warning flare on an issue the restaurant industry has only recently begun to widely grapple with: The success of chefs—too often white and male—has usually rested on the labor of the same workers of South and Central American origins that Bourdain championed (as well as those of African and Asian heritages). He would return to that point many times. In 2012, he tweeted: “Let’s play a game. Count the Mexicans at the James Beard awards.” In 2015, he denounced Trump’s attacks on immigrants, predicting a calamity for the restaurant industry if mass deportations occurred.

Well, calamity hit restaurants in 2020, and I keep thinking about Bourdain’s celebration of his colleagues down the wage chain. As much as owners and operators have suffered this year, surely Latino workers suffered more. Nationally, they represent nearly 19 percent of the population but 27 percent of restaurant employees. In Colorado, 21 percent of the population is Latino—that number jumps to 34 percent in the Denver metro area—with Hispanic or Latino people holding 25.4 percent of restaurant jobs in Denver, Aurora, and Lakewood. When I talked to Lorena Cantarovici, the Argentinian owner of Maria Empanada, in April, she said, “We are laying off people from the lowest income brackets in the state. Laying off a dishwasher is hard. We need to do something to make them not feel abandoned.”

It’s true that in the past few years, recognition of the roles of women and people of color, at least at the chef level, has increased, and there has been fitful attention paid to pay equity. After much criticism, the James Beard Foundation, whose award deliberations I have witnessed from the inside, has become more consciously diverse—yet this year’s awards were canceled, according to the New York Times, in part due to a lack of diversity among the to-be-announced winners. Locally, chefs of color are beginning to get their due, with the rise of stars like Cantarovici; James Beard–nominated Dana Rodriguez of Work & Class and Super Mega Bien and Tommy Lee of Uncle and Hop Alley; Theodora and Sylvester Osei-Fordwuo of African Grill & Bar; and others.

What Bourdain stumped for in Kitchen Confidential was the value of labor and the richness of the American restaurant kitchen subculture. The coronavirus crisis has revealed a hard truth, though: In Congress, the hospitality industry seems to be regarded as a sort of servant sector of the domestic economy, appreciated but not taken seriously. Airlines were given a bailout, while, at press time, legislation for relief specific to the much-larger restaurant industry was stalled.

COVID-19 will leave restaurants in a hole made deeper by this neglect. It will take years for businesses to recover, with many unseen casualties—disproportionately, the people who work the hardest and earn the least amount of recognition. In Denver, the biggest challenge will continue to be pay equity, because I doubt that minimum-wage increases, without subsidies from the state, will be viable.

Bourdain said his life was “a happy, stupid, wonderful confluence of events,” and his ability to appreciate his journey in the context of regret resonates right now. That quote comes from one of his most moving episodes of No Reservations, in season seven (available online). It involved a return trip to Cambodia that was a televised mea culpa for a Cambodian episode of A Cook’s Tour that he had made for the Food Network a decade earlier.

In 2000, Cambodia was incomprehensibly damaged by the war and genocide of the 1970s. Bourdain had gone there, in his words, with a “romantic-slash-tragic, narcissistic notion of the type of place I wanted to see and experience…completely inappropriate.” He went back in 2010 to listen, spending much of his time with women fighting for social justice and human rights. He managed something that I remember fearing impossible: to weave the theme of food and travel into a program that grappled with the extinguishing power of evil. “The food that I used to find with my mother is no longer there,” one woman told Bourdain over an open-air lunch of river crabs and fresh peppercorns. “The noodles that used to be made by the Chinese…like my grandparents, are not there. Killed.” Eschewing his earlier hubris, Bourdain constructed a message of hope amid loss in the shadow of injustice.

I wonder if Bourdain would remain as beloved today as he was at the time of his death, or if the Twitterati might have taken a swipe even at him. At one point in his redemptive Cambodian program, he was blessed by a man who sold him food in an outdoor market—Happiness and long life, maybe 100 years! “I don’t want to live that long,” Bourdain mused. That much we learned was true. But as his journey unfolded, he made his point, and it’s there for all of us to see, and act upon.