The Local newsletter is your free, daily guide to life in Colorado. For locals, by locals. Sign up today!

“People swear that our beans just taste better,” says Denise Pribble, who’s wearing a magenta sweatshirt and earrings that match her cropped burgundy hair. The 64-year-old daughter of a pinto bean farmer, Pribble owns and manages Adobe Milling Company, a retail store and processing plant that cleans, bags, and distributes many of the beans grown around Dove Creek, 35 miles northwest of Cortez. Whitewater paddlers know Dove Creek as the jumping-off point for float trips on the Dolores River, which flows through a deep canyon on the town’s eastern border. Food lovers, however, recognize Dove Creek as the “Pinto Bean Center of the World.”

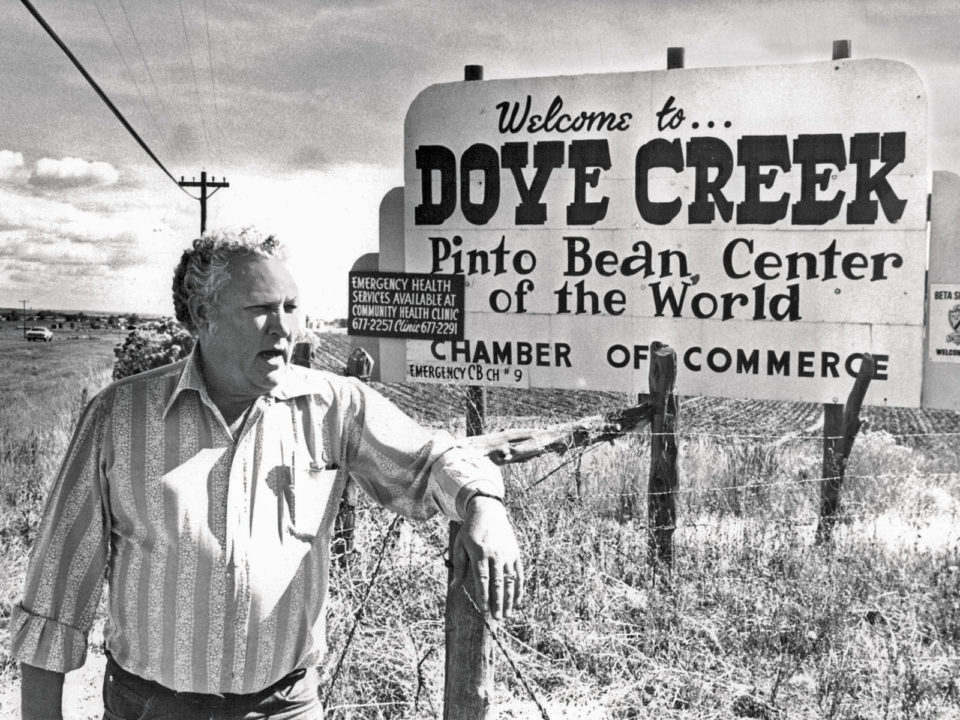

That’s the slogan that once welcomed motorists to this farming community. For about four decades, starting in the 1950s, Dove Creek celebrated the supremacy of its beans with an annual recipe contest that awarded top honors to a “Pinto Bean Queen” (never mind that some ribbon- winners were men). These days, Dove Creek’s welcome sign simply announces that it’s “Somewhere Special,” but its reputation for producing premium pulses (dried seeds of legume plants) lives on.

Each year, the region reaps between three million and 30 million pounds of beans, depending on rainfall and farmers’ crop rotations. A cult following of home cooks, barbecue competitors, and restaurateurs eagerly scoops up not only the pintos, but also Dove Creek’s Anasazi, black, bolita, and lesser-known heritage varieties, all of which are ideal for winter soups, stews, and side dishes. If these beans walked on four legs, they’d be as lauded as wagyu.

The reason behind the beans’ preeminence is a matter of debate, though. “Colorado dry beans are known for their bright, vibrant color and delicious flavor,” says Bob Schork, manager of the Colorado Dry Bean Committee, which researches and promotes bean production in the state. “We believe this is due to being grown at a higher elevation than other beans in the United States.”

Pribble credits a different natural input: Dove Creek’s russet-colored earth. “Like the places that grow the best peaches, or the best corn, our soil just seems to grow the best beans,” she says as RV-driving road-trippers and locals shouldering burlap sacks of beans stream past Adobe Milling’s register.

Or perhaps, some say, Dove Creek beans are better because their theoretical roots run deeper: Ancient Pueblo people and their modern-day descendants have grown beans (as well as corn and squash) in the region for nearly 1,000 years, as evidenced by the beans and bean pots found among archaeological sites in Mesa Verde National Park and Hovenweep National Monument. Maybe this land embraces that long relationship—or maybe the magic is in the beans themselves.

Like the Ancestral Puebloans who preceded them, many Dove Creek farmers grow beans without irrigation, which allows them to develop at a more leisurely pace than amply watered plants—possibly picking up more flavor in a process reminiscent of how wine grapes reflect their terroir. Dry-farming also reduces the number of pests and diseases that attack bean plants, so growers don’t need to use fertilizers or pesticides.

These conditions combine to produce beans with thinner skins, a dream scenario for restaurant and home chefs alike, since they typically don’t need to be pre-soaked. Furthermore, bolitas, a variety long favored by communities in the San Luis Valley for its high protein content and rich taste, actually absorb seasonings through their skins when cooked, allowing flavorings to mingle with the velvety interiors.

Not all Colorado growers eschew irrigation, of course—tasty pintos, light red kidneys, yellow Mayocobas, black beans, garbanzos, and red and black-eyed peas are farmed, sometimes with supplemental water, in various corners of the Centennial State—but the dryland specimens from the southwest corner rank as the pinnacle of all pulses, particularly when they’re fresh. “Because we receive them so close to harvest, the beans impart a rich, nutty flavor,” says Holly Arnold Kinney, culinary director for the Fort, in Morrison, where chefs use Dove Creek Anasazi and pinto beans in the restaurant’s potato side dish. Plus, “the texture is creamier,” says Angelina LaRue Lopez, a recipe developer and food columnist from Idalou, Texas, who swears by Dove Creek beans’ softness and lack of chalkiness for making a classic pinto dish: refried beans.

Bessie White’s stove is covered with pots full of gently bubbling pie filling. Jars of gem-colored apricot, strawberry rhubarb, and berry jam sit in boxes on the floor, awaiting delivery to Cortez’s Saturday farmers’ market. At 91 years old, White still delivers her homemade goodies to the produce stand she’s worked since the 1970s, when she and her sister founded the outdoor bazaar. But White doesn’t just deal in fruit; she also sells dry-farmed beans grown by her son and a grandson. Says White: “There is nothing better than a pinto bean.”

White, however, has a unique story about another pulse for which the area is widely known. In 1973, she says she was working at the local elementary school when a student showed up with a handful of pretty beans she’d found among nearby Native American archaeological sites. “There were burial sites all over the place, and you’d uncover them when you plowed your fields. The student’s dad was digging up a ruin and found a pot of beans,” says White, who planted some in her garden. She ended up with a quart-size harvest of brilliant red-and-white-speckled beans.

The variety—which may have originated in the Lukachukai Mountains of northeastern Arizona, despite White’s memory of them being found in what is now Hovenweep National Monument—ultimately became known as Anasazi. Although the word was long used to describe the Ancestral Puebloans, modern-day Pueblo tribes have pointed out that it’s a derogatory term from the Navajo language. As such, the people are now referred to as the Ancestral Puebloans, while the slightly sweet, fast-cooking bean is stuck with a moniker that loosely translates to “enemy ancestors.”

Despite its name, the Anasazi bean is a much less formidable foe to the human gastrointestinal system than many other varieties. Containing just 25 percent of the gas-producing compounds found in most beans, Anasazis trigger far less flatulence than a typical pinto. Sensing commercial potential in the rediscovered variety, Ernie Waller, who owned Adobe Milling before Pribble and her husband purchased the business in 2003, obtained a trademark for the Anasazi bean in 1989. Call it Anglo appropriation or a serendipitous, if culturally insensitive, chain of events that likely saved the variety from extinction; either way, the trademark protects the seeds’ genetics and assures that only this variety is marketed under the Anasazi name.

No matter what they’re called—or which variety the nonagenarian is (still) slinging 10-pound sacks of into her black pickup truck—White says southwest Colorado’s beans have long been a delicious part of her life. And it doesn’t take much prodding for her to tout their dominance. “Yes,” she says. “I think our beans are just better.”

Visit Adobe Milling Company’s website to buy Dove Creek–grown Anasazi, pinto, and black beans in quantities ranging from one to 40 pounds, or call 800- 542-3623 to order over the phone.